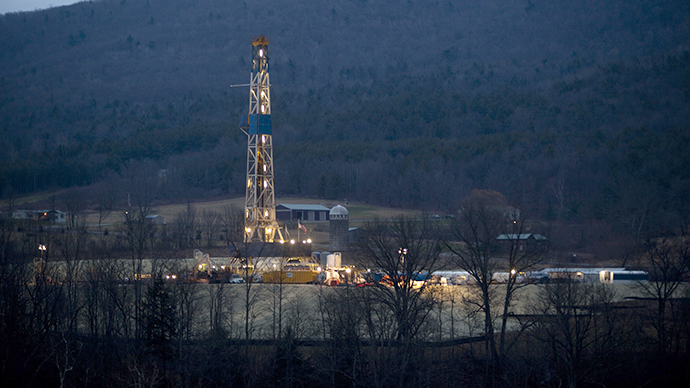

‘Alarming’ presence of radioactivity found by Pennsylvania fracking wastewater study

Researchers have found high levels of radioactivity, salts, and metals in water and sediment located downstream from a treatment facility which processes fracking wastewater from oil and gas production sites in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus shale formation.

A Duke University team analyzed water and sediment samples from

the Josephine Brine Treatment Facility in Indiana County,

Pennsylvania, finding radium levels 200 times greater than

samples taken upstream from the plant and far higher than what’s

allowed under the Clean Water Act.

Radium is a radioactive metal that can cause diseases like

leukemia and other ill-health effects if one is exposed to large

amounts over time.

The treatment facility processes flowback water - highly saline

and radioactive wastewater that resurfaces from underground after

being injected into rocks in the fracking, or hydraulic

fracturing, process.

Fracking is the extraction of oil and gas by injecting water to

break rock formations deep underground. Use of the process has

increased rapidly in the US in recent years, yet scientists who

have studied the practice warn of climate-damaging methane emissions and radioactive effects that come

with it.

The study was published Wednesday in the Environmental Science

and Technology journal. It focuses on two years of tests on

wastewater flowing through Blacklick Creek from oil and gas

production sites in western Pennsylvania’s Marcellus shale

formation.

For two years, the Duke team monitored sediment and river water

above and below the treatment plant, as well as discharge coming

directly from the plant, for various contaminants and levels of

radioactivity. In the discharge and downstream water, researchers

also found high levels of chloride, sulphate, and bromide, which

can interact with chlorine and ozone - used to disinfect river

water for drinking -to create a toxic byproduct.

“The treatment removes a substantial portion of the

radioactivity, but it does not remove many of the other salts,

including bromide,” said study co-author Avner Vengosh, a

Duke professor of geochemistry, adding that traditional

facilities like Brine aren’t made to remove these contaminants.

Though the Brine treatment facility strips some radium from

fracking wastewater, high levels of metal still accumulate in

sediment.

"The occurrence of radium is alarming - this is a radioactive

constituent that is likely to increase rates of genetic mutation"

and can be "a significant radioactive health hazard for

humans," said William Schlesinger, a researcher and

president of the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, who wasn't

involved in the study.

Researchers believe the contaminants come from fracking sites

because the Brine facility treats oil and gas wastewater which

has the same chemical features as rocks in the Marcellus shale

formation.

Some fracking wastewater is shipped by oil and gas companies to

treatment plants like Brine to be processed and released into

waterways. But most wastewater is reused for more fracking, Lisa

Kasianowitz, an information specialist at the Pennsylvania

Department of Environmental Protection, told ClimateCentral.org.

Kasianowitz said the treatment facility is handling

"conventional oil and gas wastewater in accordance with all

applicable laws and regulations.”

Vengosh said that the research indicates that similar

contamination may be happening around other fracking locations

along the Marcellus shale formation in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and

New York.