California prisons punish inmates by racial bloc, not offense

Are California prisons determining inmates' punishments based solely on their race? Though it’s not said to be official policy, a new report shows that at least five state prisons maintain a color code system to racially segregate their populations.

According to a number of documents, including a state response, collected by the ProPublica investigation, some California prison facilities separate and label prisoner blocks by ethnicity in order to “provide visual cues that allow prison officials to prevent race-based victimization, reduce race-based violence, and prevent thefts and assaults.”

Though few would argue that maintaining a prison population as large as California’s is an easy task, organizations like the ACLU and the Prison Law Office are fighting the practice, arguing that besides being an uncomfortable reminder of the days of racial segregation, it is an ultimately ineffective way to maintain order.

One document collected by ProPublica describes color signs placed above cell doors at men’s prisons across the state: blue for black inmates; white for white; red, green or pink for Latino; and yellow for everyone else.

“Rather than targeting actual gang members, they assume every person is a gang member based on the color of their skin,” said Rebekah Evenson, an attorney with the Prison Law Office.

According to an analysis conducted by Evenson’s group, nearly half of the 1,445 security lockdowns enacted between January 2010 and November 2012 impacted specific racial or ethnic groups. The report showed that Hispanics were the most habitual target, while inmates categorized as “other” were least likely to be restricted.

Though correctional officials with the state of California deny racial targeting, some inmates have come forward with complaints, and in 2011 filed a class action lawsuit claiming racial discrimination.

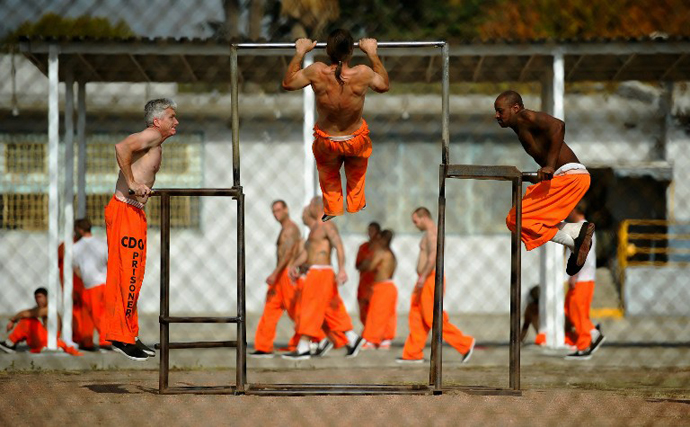

Robert Mitchell, an inmate at High Desert State Prison, testified that he had been swept up into recurring lockdowns because he is black, and had suffered muscular atrophy and pain as he was prevented from exercising a leg injury.

Hanif Abdullah, another black inmate suing the state, says he was placed on “modified programming” multiple times, and was kept from attending religious services as well as receiving adequate health care. Modified programming refers to security situations requiring that inmates be prohibited from seeing visitors, visiting the prison yard, or even from attending classes and drug rehabilitation meetings.

Though the state’s total prison population recently dropped, with nearly 200,000 inmates the system is still at 150 per cent of its maximum capacity.

In 2005, the US Supreme Court ruled that racial classifications must be limited to a narrowly defined and compelling “state interest.” In its opinion brief, which pertained to racially segregating prisoners prior to entering a new correctional facility, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote, “When government officials are permitted to use race as a proxy for gang membership and violence ... society as a whole suffers.”

Currently, California is the only state in the country known to

employ race-based lockdowns, according to the ACLU National Prison

Project.