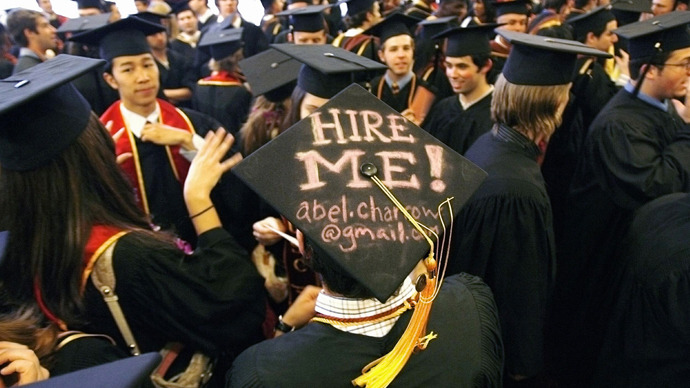

The number and value of overdue student loans has reached an all-time high in the US as nearly a third of 20- to 24-year-olds are currently unemployed, according to a report by the Department of Education.

With continued concern regarding rising college costs, the

amount of outstanding student loans has now reached $1 trillion,

making that the largest category of consumer debt in the US aside

from home mortgages.

According to the new report, eleven per cent of school loans - one

hundred and ten billion dollars' worth - are now seriously

delinquent, meaning at least 90 days past due. That is a sharp

increase from the 6 per cent reported in the first quarter of

2003.

The long-term consequences of the school loan repayment burden can

include a graduate’s choice of jobs, as well as the ability to buy

a home.

A tight job market and a continued increase in the cost of higher

education leave many to question the very value of obtaining a

college degree, as opposed to more vocationally oriented

training.

“Today’s economy puts young

graduates in a difficult position,” Jack Buckley,

commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics, which

published the report, said in a statement.

“A college diploma no longer

guarantees a direct pathway to the middle class, making it harder

to justify the expense of a degree.”

Still, as Bloomberg reports, the employment rate for college

graduates in the US is 87 per cent, as compared with 64 per cent

for those with only a high school school diploma.

One item which seems to have been eclipsed in recent partisan wrangling in Congress is a looming rate increase in federal student loans, which is set to double to 6.8 per cent on July 1 assuming there is no intervention. That rate increase would impact the more than 7.4 million students who can currently apply for a 3.4 interest loan.

On Thursday, the House voted along party lines to push forward a Republican initiative to intervene in the interest rate increase, though the specifics of the plan is sure to have the student loan debate take center stage in coming weeks.

The new bill would allow student lending rates to reset every year, tied to the interest rate of a 10-year US Treasury note, plus 2.5 percentage points for federal Stafford loans. According to the Congressional Budget Office, that means that the projected rate increase on those loans would rise to 5 per cent in 2014, and 7.7 per cent in 2023.

“Who’s going to set interest rates, politicians here or the markets?” asked Representative John Kline, Republican of Minnesota.

The legislation would cap Stafford loans at 8.5 per cent, with a higher maximum of 10.5 per cent for graduate loans.

Democrats, who are thus far opposing the Republican plan, prefer to extend the current Stafford subsidized rate - subsidized meaning that interest is not accrued while a student is enrolled - at a cost of $8.3 billion to the federal government, which would in theory be paid for by closing tax loopholes.

According to The New York Times, some Democrats want to take things even further. Senator Kirsten Gillibrand has proposed locking in a 4 per cent rate for all student loans, and allowing graduates with higher interest rate loans to refinance at that rate.

President Obama has already put forth his own proposal, which, like the Republican plan would tie student loan rates to the Treasury’s borrowing costs, but would then fix that rate for the life of the loan, rather than resetting each year. The administration’s plan would also cap loan repayments at 10 per cent of a student’s income.

Delinquency rates on existing student loan debt suggests that, whatever solution Congress ultimately selects to follow, it will have to make loan repayments feasible as higher education costs continue to increase while wages have stayed roughly the same for several decades.

In addition to the Republican-sponsored bill HR1911, there are at least eight other bills aimed at modifying or freezing interest rates on federal school loans before the July 1 deadline.

The White House on Wednesday threatened to veto the Republican bill, arguing that it would not guarantee low rates due to its yearly reset.

Meanwhile, Mark Kantrowitz, publisher of Edvisors.com, says the fight over subsidized loan rates “is a distraction from the real problem, which is the amount of debt, not the cost of debt.”

Kantrowitz may well have a point. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, a recent study from Fidelity found that “70 per cent of the class of 2013 is graduating with college-related debt – averaging $35,200 – including federal, state and private loans, as well as debt owed to family and accumulated through credit cards.”