875,000 left in bureaucratic black hole that is US terror watchlist system

Published 14 Mar, 2014 22:49 | Updated 14 Mar, 2014 22:49

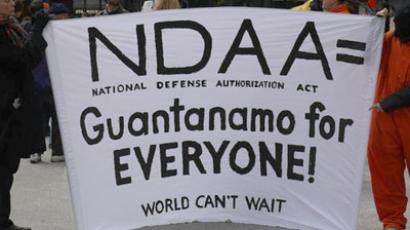

The US had 875,000 people in its terrorist watchlist system as of December 2012. Those secretly blacklisted have no real path to challenge their status, states a new report, thus indefinitely restricting those listed from travel or simply getting a job.

Hundreds of thousands of Americans and foreigners languish in the watchlist system, considered “known or suspected terrorists” based on secret rules and evidence that are basically impenetrable should the average suspect attempt to contest them, says a new report by the ACLU that highlights these challenges.

The US terrorist watch list system, which is shared with state and local law enforcement agencies, can stifle overseas travel, the ability to obtain a US visa or entry into the US, and can lead to invasive screenings or detentions by authorities at airports and the like. This is not to mention the social pressure of being considered a terror suspect by the US, which can lead to a host of problems ranging from separation from family to ostracization from a community or place of employment, for example.

Despite the endless effects that can stem from being placed in the watchlist system, the US has not taken proper care to avoid the basic fairness principle of innocent until proven guilty, according to the ACLU.

“It has placed individuals on watchlists, and left them there for years, as a result of blatant errors,” the ACLU says of the bureaucratic punitiveness of the system. “It has expanded its master terrorist watchlist to include as many as a million names, based on information that is often stale, poorly reviewed, or of questionable reliability. It has adopted a standard for inclusion on the master watchlist that gives agencies and analysts near-unfettered discretion. And it has refused to disclose the standards by which it places individuals on other watchlists, such as the No Fly List.”

There is no clear way to “redress” the US government for this process should one challenge their inclusion in the watchlist system – that is, if they can ever obtain proof that they’re even included in this Kafkaesque system.

“Even after people know the government has placed them on a watchlist—including after they are publicly denied boarding on a plane, or subjected to additional and invasive screening at the airport, or told by federal agents that they will be removed from a list if they agree to become a government informant—the government’s official policy is to refuse to confirm or deny watchlist status,” the ACLU says.

“Nor is there any meaningful way to contest one’s designation as a potential terrorist and ensure that the U.S. government, and all other users of the information, removes or corrects inaccurate records.”

Take the case of Rahinah Ibrahim, a Stanford Ph.D. student and Malaysian citizen. Nine years ago, Ibrahim tried to board a flight from San Francisco, California to Hawaii with her teenage daughter when she was detained by authorities, interrogated for hours, and told she appeared on a no-fly list. Ultimately she was cleared for air travel, but two months later was instructed that her visa had been revoked due to a US terrorism law. She has spent much of the last nine years in Malaysia, communicating with colleagues at Stanford and across the US using the phone and internet.

In December, US District Judge William Alsup wrote that Ibrahim is "entitled by due process to a ... remedy that requires the government to cleanse and/or correct its lists and records of the mistaken information,” and agreed that the rules surrounding adding and maintaining names on federal watchlists include serious hurdles that prevent innocent people from learning about their status. Both the judge and the government admitted at trial that Ibrahim did not and does not pose a threat to America.

In February, Alsup followed up with a heavily-redacted 38-page order that said Ibrahim’s woes may never have occurred had an FBI agent not checked the wrong box while filling out paperwork almost a decade ago.

Ahead of Ibrahim’s planned flight to Hawaii, the order acknowledges, she met with FBI Special Agent Kevin Michael Kelley, who at that same time was involved in what the court called a “mosque outreach program” that provided “a point of contact for mosques and Islamic Associations” with federal agents. Kelly’s role involved recommending people to be added to various government watchlists, and according to the court he made a mistake while doing paperwork regarding Ibrahim.

“Agent Kelley misunderstood the directions on the form and erroneously nominated Dr. Ibrahim to the TSA's no-fly list [redacted],” Judge Alsup admitted in the February order. “He did not intend to do so. This was a mistake, he admitted at trial. He intended to nominate her to the [longer redaction]. He checked the wrong boxes, filling out the form exactly the opposite way from the instructions on the form. He made this mistake even though the form stated, ‘It is recommended the subject NOT be entered into the following selected terrorist screening databases.’”

“Based on the way Agent Kelley checked the boxes on the form,” the judge continued, Ibrahim “was placed on the no-fly list [longer redaction]. So, the way in which plaintiff got on the no-fly list in the first place was human error by the FBI.”

The ACLU suggests the US government “reform” this vast, unaccountable system by narrowing the criteria for landing in the watchlist system; applying a more rigorous, fair review standard for contesting suspect status; and limiting how far-reaching the effects are for those ultimately not proven to have committed any crime.