Texas could set new standard on email privacy laws

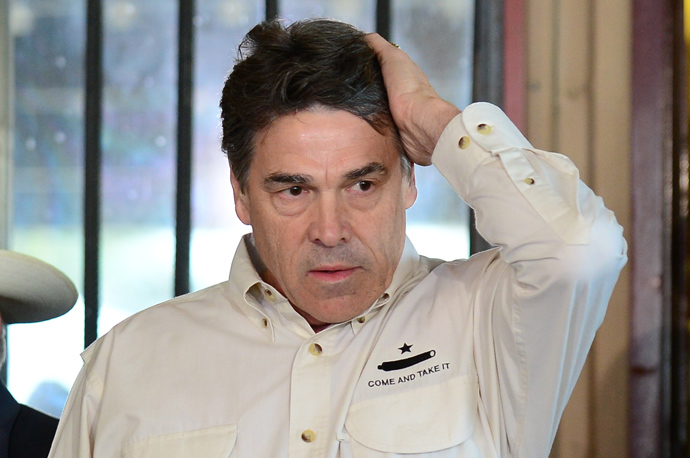

Texas could soon end up leading the US in email privacy regulations, assuming Governor Rick Perry allows a new bill compelling law enforcement agencies to obtain a warrant prior to accessing online correspondence to become law.

The new bill (HB 2268) has been sent to the governor, and looks to provide a roadmap to updating the 1986 Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA) which requires federal law enforcement to obtain warrants only when accessing recent emails, before they are accessed by recipients.

Online privacy activists such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the ACLU have long argued that ECPA, which essentially allows unopened emails over 180 days old to be accessed without a warrant, is woefully outdated.

Considering the current prevalence of electronic mail, it seems that the Department of Justice also agrees that ECPA should be modernized to better reflect current privacy concerns.

In a written testimony presented to the House in March of 2013, Acting Assistant Attorney General Elana Tyrangiel outlined the legislation as it exists today:

“We agree, for example, that there is no principled basis to treat e-mail less than 180 days old differently than e-mail more than 180 days old. Similarly, it makes sense that the statute not accord lesser protection to opened e-mails than it gives to e-mails that are unopened. Acknowledging that the so-called ‘180-day rule’ and other distinctions in the [Stored Communications Act, a sub-section of ECPA] no longer make sense is an important first step. The harder question is how to update those outdated rules and the statute in light of new and changing technologies while maintaining protections for privacy and adequately providing for public safety and other law enforcement imperatives.”

The Texas governor now has until June 16, 2013 to either sign the new law, which passed both chambers of the state legislature without a single dissenting vote and is slated to take effect on September 1, 2013 - or veto.

According to the Texas Electronic Privacy Coalition, one of the main backers of the new law, at the time that ECPA was introduced no one conceived that data would be stored for more than six months. Based on technology at that time, data older than this was considered “abandoned.”

“Most people are shocked when they learn that law enforcement or government agencies like the Department of Insurance can get the contents of email or find out everywhere you’ve been for the past two months by going directly to your service provider,” said Greg Foster, of EFF Austin.

As Ars Technica notes, however, the new Texas bill would not protect individuals from federal investigations, though the precedent set by the legislation could well set the standard for other states around the US, and trickle its way to federal reform of ECPA.

In addition to making all private email access subject to a warrant request, the new state law would also pertain to detailed cell-phone location data, another key issue in the current debate over modernizing online privacy laws.

In April, US District Judge David Campbell ruled in United States v. Rigmaiden that federal investigators could present evidence gathered via the use of a wireless access card purchased by a plaintiff, which had at the request of the FBI been reprogrammed by the provider, Verizon, to provide location data to a “spoofed cell tower.”

Modifications to state law could well mean that local law enforcement would need to go through additional legal motions before obtaining a suspect’s wireless geo-location data. It might, ultimately, also call into question the use of technology like Stingray (or IMSI catcher) which allows law enforcement agencies to “spoof” real cell towers in order to collect data from all nearby mobile devices and sift through to find a suspect.

Just how powerful the new Texas privacy bill may ultimately be if signed into law by Governor Perry remains to be seen, though backers like the ACLU believe that even a symbolic step could be key in securing federal Congressional support.

“It's always good to see states passing pro-privacy legislation because it sends a signal to Congress. It sends a signal to conservative members who might not yet be on board that this is something being supported in their own states and it helps the courts to see that this is a safe space to venture into. When cities and states start protecting e-mail, then judges may feel like there is a reasonable expectation of privacy,” said Chris Soghoian, an ACLU senior policy analyst who spoke to Ars Technica.