In anticipation of international military drills in the Arctic this year, the US Navy has developed a detailed plan to establish a massive presence in the region. The road map says urgent investments are required to avoid higher future costs.

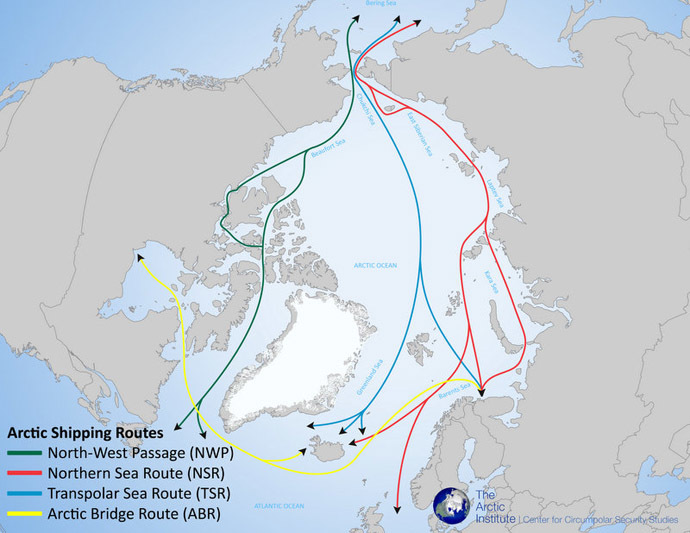

The road map acknowledges that by 2020 the Bering Strait will have ice-free conditions for about 160 days a year, whereas by 2025 the now-hypothetic Transpolar transit sea route through the central part of the Arctic Ocean might become open for up to 45 days annually.

The document specifies a large number of detailed tasks and deadlines the US must meet to compete on equal footing with other Arctic nations, already lining up for tough competition for natural resources under the Arctic seabed.

For example, total deposits of hydrocarbons in the Arctic have been valued at over $1 trillion.

The plan includes deep research into the Arctic’s environment, including into ice conditions, sea levels and weather forecasting.

“The Arctic is all about operating forward and being ready. We don't think we're going to have to do war-fighting up there, but we have to be ready,” the US Navy's top oceanographer and navigator Rear Admiral Jonathan White told Reuters.

Evaluation of the already existing infrastructure, such as ports, airfields and service structures, as well as estimates of hardware needed, such as communication satellites and icebreakers, has also been included.

“We don't want to have a demand for the Navy to operate up there, and have to say, ‘Sorry, we can't go,’” said White, who also heads the US Navy's climate change task force.

But the document does not specify how much money implementing the plan will require.

The US needs Arctic-class ice-breakers, port infrastructure, satellite communication systems specialized for the polar region and much more.

For example the US Coast Guard needs a modern powerful icebreaker, construction of which is estimated $1 billion. This is far less than the cost of the newest supercarrier, the USS Gerald R. Ford, but the money has not been allocated so far.

“We're trying to use this road map to really be able to answer that question,” White said, warning that it was better to invest as soon as possible to avoid “bigger bills in the future.”

White said that the Office of Naval Research and the Pentagon's Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency are already funding numerous Arctic-focused projects, predicting more public-private projects would come in the next few years, despite the growing pressure on the US military budget.

“As far as I'm concerned, the Navy and Coast Guard's area of responsibility is growing,” White said. “We're growing a new ocean, so our budget should be growing in line with that.”

Arctic Ocean

Area: 14,056,000 km2

Coastline: 45,390 km

Maximum depth: 5,450 m

Water temperature: −1.8 °C

If the US plans to operate in ice-free, but still extremely harsh conditions in the Arctic by 2030, it should hurry up and face technological and financial challenges, White said.

“If we do start to see a rush, and people try to get up there too fast, we run the risk of catastrophes,” he said, calling the private sector to invest and move into the region. “Search and rescue in the cold ice-covered water of the Arctic is not somewhere we want to go.”

Natural resources

Experts say that new sea routes and natural resources under the Arctic seabed will be controlled by those who get ready to exploit them in advance, and that is where the US is already lagging behind.

Norway and Russia, with which the US Navy will hold joint drills this summer, can consider themselves well prepared for the Arctic race already under way.

The US currently has fewer operational ocean-class icebreakers than practically any other Arctic nation. Countries such as Canada, Denmark and Norway all possess several ice-breaking vessels, but all of them are limited to less than 10 such ships.

Today it is mostly the US nuclear submarines and UAVs that are marking the US’s presence in the Arctic.

Russia has the longest sea border in Arctic, which determine possession of a huge ice-breaking fleet. Russia possesses well over 40 ice-breaking vessels, of them 11 nuclear powered operated, and is actively constructingnew ones to develop the Arctic region and in particular the Northern Sea Route, the shortest way from Asia to Europe.

To ensure full control over the promising trade route through Arctic waters, the Russia military resumed a permanent Arctic presence last summer.