British World War II veteran Victor Gregg might not be alive today were it not for the Allied bombardment of Dresden. But the now-97 year old finds it difficult to reconcile the hellish events of February 13, 1945 with victory.

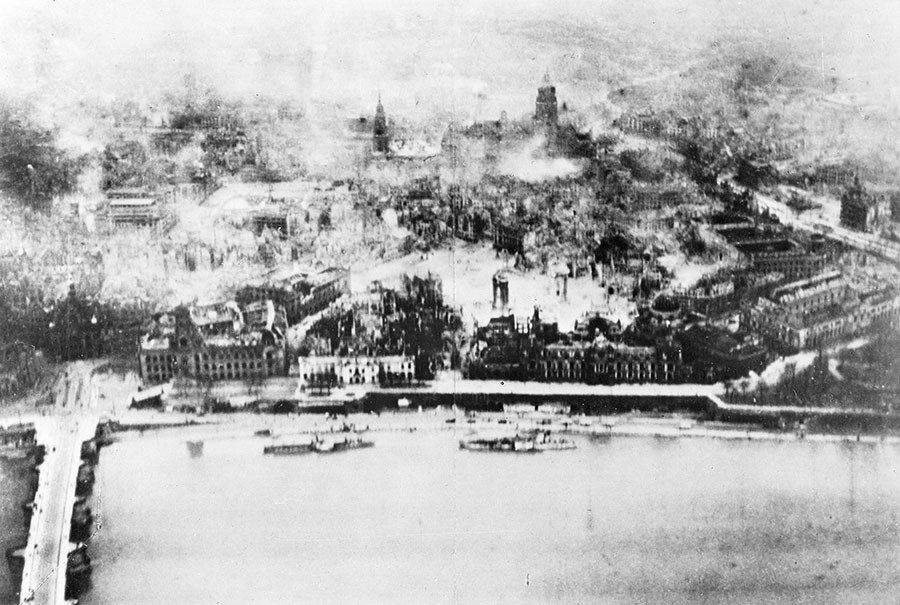

On that night, around 800 Allied aircraft filled the air above Dresden and proceeded to drop 1,500 tons (metric) of high explosives and incendiary canisters, setting the city ablaze and turning it into a scene from hell. Some 25,000 people perished in the bombing.

The catastrophic aerial attack focused on the historic German city after Britain’s Royal Air Force identified the area as a key transportation and industrial hub for Nazi Germany.

More than 1,600 acres (6.5 sq km) within the city were either flattened or gutted, and a final death toll was tallied only in 2010, by the Dresden Historians’ Commission.

More than seven decades on from the Allied bombing, one of the event’s survivors, a former paratrooper, describes the late night blitz as “more than” a war crime. Victor Gregg says the events left him psychologically scarred, contributing to “50 years of traumatic stress.”

‘Everything was alight’

After being captured at Arnhem in the Netherlands, Gregg was one of the few Allied troops on the ground during the bombing of Dresden.

“I was in a Straflager – a special punishment cell – with my mate where we were waiting to be shot. We were supposed to be put against a wall the next morning,” Gregg told RT.com.

As air raid sirens announced their arrival, De Havilland Mosquito planes from the Royal Air Force (RAF) dropped flare markers on the city below. By now the people of Dresden would have grown used to wailing sirens, but Gregg says no-one was prepared for the firestorm and asphyxiating conditions which swept through large parts of the city.

The 97 year old said when a bomb hit the POW site he was thrown “over the other side of the building” but miraculously survived: “My mate got killed there...but I managed to get out. There was rubble everywhere, bodies everywhere. Bits of arms and legs. About 30 of us got out of the building, out of about 300. Everyone else was killed.”

To escape being crushed by falling masonry, Gregg and a group of fellow survivors bunkered down in an open square. Nearly two hours later, a second and more devastating wave of bombs rained down just as people began leaving their shelters.

“When the second wave came over they were all out in the open. The planes were dropping 4,000lb [1.8 metric tons] canisters and when they hit the ground anything within about 400 yards was immediately incinerated.”

Wearing a pair of German clogs and a coat given to him by a firefighter, Gregg eventually slipped over the River Elbe to join up with Russian forces. He was reunited with British personnel 10 weeks later, with the Allies on the cusp of victory.

Gregg, who has detailed his extraordinary military experience in the books ‘Rifleman’ and ‘Dresden - A Survivor’s Story’, says the war left its mark: “It made me quite callous. You’re living two lives, that’s what it does to you because nobody can go through that experience and come out of it with their brain in one piece.”

‘Chillingly ruthless’

British historian Frederick Taylor told RT in an email that Dresden’s bombardment would almost certainly be considered a war crime today. He adds that, militarily speaking, the city was important to Nazi Germany but that it is “impossible to be proud of Dresden and similar chillingly-ruthless attacks during World War II.”

He says the moral question surrounding Dresden is not a simple one, as the bombs came amid a brutal war and in February 1945 “thousands were still dying everyday in conflict and massacres carried out by the retreating Nazis.”

“Contrary to a common assumption that it was a ‘city without industry’, Dresden, though architecturally outstanding, was indeed in strict terms a legitimate target – or at least, substantial parts of it were.

“It was situated athwart main rail lines running north to south and east to west. The city’s garrison was the second largest in Germany,” he told RT.com.

“Some 70,000 of its around three quarters of a million inhabitants were involved in war industries. None of all this means, of course, that Dresden had to be attacked the way it was,” he added.

Arnd Bauerkämper, a professor of history at the Friedrich Meinecke Institut in Berlin, is of a similar view.

“There was war industry in Dresden and plants that produced for the German war effort. Dresden was also one of the transport centers for sending German forces to the Eastern front,” he said. “Even if [the Allies] had these objectives [to weaken German military capabilities] they did go too far because there were three major air raids on a city that was largely unprotected.”