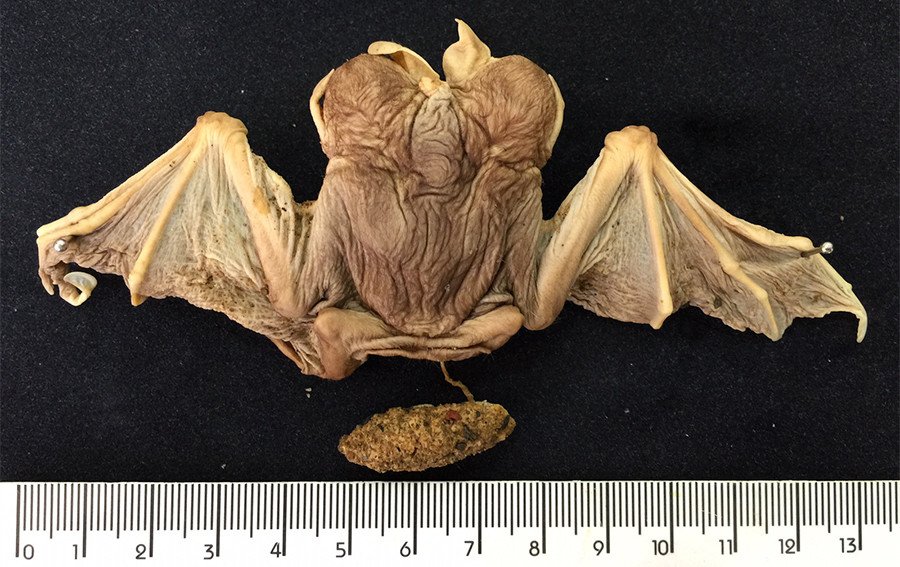

Conjoined baby bats stun Brazilian scientists (PHOTOS)

The corpses of rare conjoined bats found under a mango tree in southeastern Brazil 16 years ago have been analysed by “completely astonished” scientists.

This is only the third time the phenomenon has been reported in scientific literature – earlier records of conjoined pairs were published in 1969 and 2015.

READ MORE: 'World’s first': 2-headed porpoise caught off coast of the Netherlands (PHOTOS)

The twin male conjoined bats were already dead when they were found in a Brazilian forest in 2001 and donated to the Laboratory of Mastozoology at the Rural Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

Marcelo Rodrigues Nogueira, who led the study of the mammals, explained his shock at the find to Live Science, saying: "I have handled many bats, some with very impressive morphological characters, but none as surprising as these twins."

The ‘Siamese’ bats are ‘dicephalic parapagus conjoined twins,’ meaning they are connected side-by-side along their trunks.

The animals had separate heads and necks, but X-rays revealed their spines eventually converged.Ultrasound images showed the bats also had separate but similarly sized hearts.

The placenta was still attached to the pair, leading researchers to surmise they were either stillborn or died at birth. Based on their physical characteristics the scientists determined they were most likely ‘Artibeus’ bats.

The total breadth of the twins, including wingspan, measures about 13cm.

While incidences of conjoined twins are well-studied in humans, it is rarely reported in wild animals.

The prevalence among humans varies depending on location, ranging from 1 in 2,800 in India to 1 in 200,000 in the US, while survival rates range between 5 percent and 25 percent, according to the University of Maryland Medical Center. This rate is believed to be lower in the animal world.

Bats are one of the lowest-reproducing animals in the world, typically only having one pup per litter. Therefore twins, conjoined or otherwise, are particularly rare in the species.

The team researching the conjoined bats is now confident that their study will add to greater understanding of patterns and processes behind the phenomenon.

“It is our hope that cases like this will encourage more studies on bat embryology, an open and fascinating field of research that can largely benefit from material already available in scientific collections,” Nogueira told National Geographic.