Switzerland caves in to US in tax evasion dispute

The Swiss government has agreed to meet US demands and disclose bank client names in a bid to resolve the long-standing tax-evasion dispute between the two countries, Switzerland's Finance Minister said on Wednesday.

"This is both a good and a practical solution," Eveline Widmer-Schlumpf told reporters after a cabinet meeting approved the draft accord.

The deal, which has to be approved by the parliament, will see Swiss banks turning over key information to US authorities.

"We hope that it will enable this chapter to be closed," she said, saying that it was nonetheless up to individual banks to decide if they wanted to cooperate with US authorities.

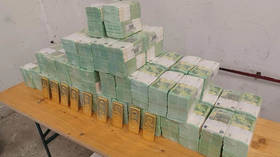

Swiss banks have earned a reputation of keeping personal information of account holders secret. The tradition of banking secrecy helped build the country's $2 trillion financial industry.

On Tuesday, the Swiss government ordered its third largest private bank, Julius Baer, to hand over data on US clients. Confidential information is due to be passed on to US tax authorities under the terms of an existing double taxation treaty between the two countries. Julius Baer replied it would provide the necessary data, though it didn’t reveal how many clients were involved.

At the end of April 2013, Julius Baer Group’s assets under management amounted to 220 billion Swiss francs ($207.7 million). The 16 per cent increase from the end of 2012 was in many ways thanks to its acquisition of Bank of America Corp.'s (BAC) Merrill Lynch wealth-management business outside of the US. Total client assets grew by 12 per cent to 309 billion Swiss francs.

Over a dozen Swiss banks are said to be under the US investigation, according to Reuters, with the authorities searching for funds hidden in bank accounts of giants like Switzerland's second largest-bank Credit Suisse. The US Attorney's Office has been reportedly investigating Credit Suisse AG over mortgage-backed securities sold by the bank. In November, the bank settled the case without admitting wrongdoing and it agreed to a $120-million settlement with the US Securities and Exchange Commission over civil charges stemming from the bank's sale of risky mortgage bonds to investors before the crisis.

In January Switzerland’s oldest private bank, Wegelin & Co, said it would close down for good after over 250 years of service, following its guilty plea to charges of helping prosperous Americans hide more than $1.2 billion from the Internal Revenue Service through secret accounts.

A managing partner at the bank, Otto Bruderer, confirmed in court that "from about 2002 through about 2010, Wegelin agreed with certain US taxpayers to evade the US tax obligations of these US taxpayer clients, who filed false tax returns with the IRS."

While it was unclear whether the bank was required to expose the names of the American clients who held secret Swiss bank accounts, "what is clear is that the Justice Department is aggressively pursuing foreign banks who [sic] have helped Americans commit overseas tax evasion," a former federal prosecutor involved in other Swiss bank investigations, Jeffrey Neiman, told Reuters.

The US authorities’ biggest success so far came in 2009 when Switzerland’s largest bank, UBS, agreed to give away some 4,450 client names and paid a $780 million settlement after admitting to selling tax-evasion services to Americans.