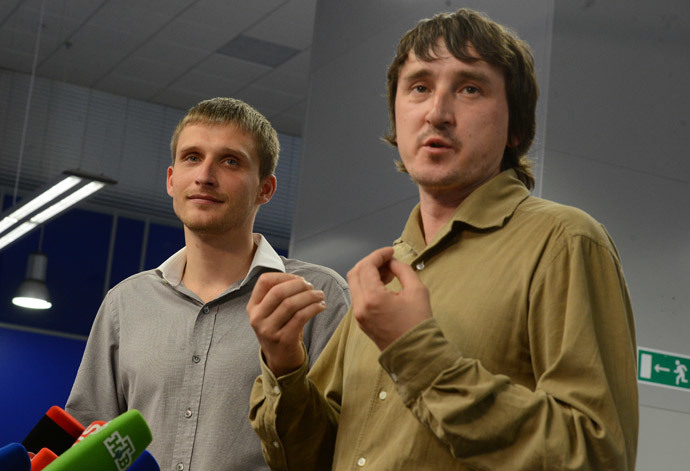

'Kept in dugout, tied up with sacks on heads': Russian journos on Ukraine detention

Two Russian journalists held in detention in Ukraine for several days say they were kept in a dug-out cell with sacks on their heads, their hands and legs tied. They claim their lives were also threatened.

It all started when the two moved towards the airport near Kramatorsk to check the information provided by the locals that the Ukrainian forces had left it.

“Next to the airport, we ended up being at gunpoint by Ukrainian law enforcement officials. We raised our hands and shouted that we are journalists,” cameraman Saichenko said.

About 12 people jumped from two armored vehicles and opened fire over the journalists’ heads. They were surrounded, searched, pushed in to the armored vehicle. The military men also took their belongings.

No reasons were given for their detention, everyone just “kept poking at them with machine guns,” Sidyakin said.

“We told them we’re journalists, that we had no weapons, that we were on an official mission from our editors. But they weren’t convinced. In an hour we were pushed in the same armored vehicles and took to a field, and then loaded us into helicopters. When we arrived, we were forced to keep our heads close to the ground not to see anyone’s faces… In response to our requests to call someone, we were hit on the head,” Sidyakin added.

The journalists also said that initially, they were given “no food at all, only gave us some water overnight.”

“While we were waiting for the helicopter, we were shown an ‘Igla’ [needle] MANPAD [Man-Portable Air Defense] and told that we were Russians, and that is a Russian weapon. When they were loading us into the helicopter, they also took that weapon. All the military men were sure that they had caught separatists and terrorists who had this thing with them,” Saichenko continued.

“During the questioning, they used some ointment that was supposed to lead to some result. But there was none, so they got angry,” Sidyakin said.

“The guards told us that we would be shot down by dawn anyway, and asked us to take off our trainers so that they could have them [while they were still] clean,” Saichenko said.

The journalists said that the military men wanted them to admit that the weapon had been in their possession.

“They were trying to force us to confess that it was our MANPAD… We didn’t take any weapons in our hands, even ammunition, as it contradicts our profession,” Sidyakin said.

When asked what kind of people they saw during their detention, the journalists stressed that the contingent was most diverse at the airport.

“There were many mercenaries. There were people in uniforms uncharacteristic for Ukraine. They didn’t speak with anyone, just silently entered the HQ. It remains a mystery to us who they were.”

Despite not having heard anything spoken in English, Sidyakin said there were many people “uniformed and equipped Western-style, their behavior was strange, and so was their demeanor and the fact they weren’t talking to anyone.”

Saichenko remarked that, in his opinion, the Ukrainian army has a very disconnected structure.

“Having spent some time within the Ukrainian army and felt what it’s like, we understood that it is a very divided body. Many conscripts, including those who guarded us, complained that they should have been fired a long time ago, but haven’t been dismissed up to that moment. They complained about the quality of food,” Saichenko said.

“A young man who used to romanticize Maidan [the heart of the Kiev protest earlier in the year] was among them and he told us that now “he understands what he was caught up in…” Saichenko added.

Earlier, Saichenko said that Ukrainian law enforcement officials threatened to kill him and his colleague, reporter Oleg Sidyakin, and did everything possible to make the two would believe in the seriousness of their intentions.

Their hands were tied behind their backs, their legs were taped up, and sacks were put on their heads. The sacks were also taped up on their necks, so it was barely possible to breathe.

“My state was close to madness, it was very bad. I was hit on the head and kicked into the groin a couple of times, but I would prefer being beaten to the way we were held in that hole,” Saichenko said.

Saichenko also said that despite the hate, there was always room for hope.

“We were surrounded by hatred. Our guards believed that we were terrorists. I was told that I could be taken to the toilet and shot dead because I supposedly was trying to escape. We spent two days in that dug-out cell, and then four days in a closed room. But we still understood that we would be fought for, that our case would make it to the top. We were certain that President Putin and other leaders would fight for us,” he said.

Despite everything they’ve been through, Sidyakin and Saichenko are leaving the possibility that they will go to Ukraine to cover events there open, if the channel’s leadership approves their work trip – but not because they’re daredevils.

“I’ve always justified my presence in such places with the idea that I need to show that war is bad, that it’s suffering, death,” Saichenko stressed.

He says they signed a document which said that they, as LifeNews journalists, “pledge not to inflict any harm on Ukraine and the Ukrainian people.”

The Russian journalists for LifeNews TV channel were captured by Kiev forces near the eastern city of Kramatorsk a week ago.

They were being investigated on charges of “aiding terrorist groups,” according to Kiev authorities, who refused to give any information about their location and denied a special observer mission access to the journalists.

The accusations of illegally transporting weapons and aiding terrorism against Russian journalists are “nonsense and delirium,” President Putin said earlier, calling the situation “unacceptable” and warning that Kiev’s crackdown on reporters working in Ukraine will affect Moscow’s relations with the “new Ukrainian authorities.”

It was a plea by the UN and the OSCE that made the Ukrainian authorities change their mind and stop trying to build a case against the journalists, deputy chief of the Ukrainian Security Service (SBU) clarified.

“Ambassadors and representatives of the UN and the OSCE have turned to SBU. We decided to accommodate these two particular organizations,” Victor Yagun said at a briefing.

But according to LifeNews Channel, envoys of Chechen president Ramsan Kadyrov have led the negotiations, yet kept it away from the public as a safety precaution several days, while a plane ready to depart at a moment’s notice was for waiting for negotiations results.