Key to ultra-rare genetic disorders? Scientists create face recognition software for better diagnosis

New breakthrough face recognition software by Oxford University researchers may soon help diagnose rare genetic conditions and even give hints about ultra-rare genetic disorders.

Just like photo software used by Google, Picasa or Facebook, the computer program will be able to recognize faces in ordinary, everyday photographs, an official press-release from the Medical Research Council's Functional Genomics Unit at Oxford University said.

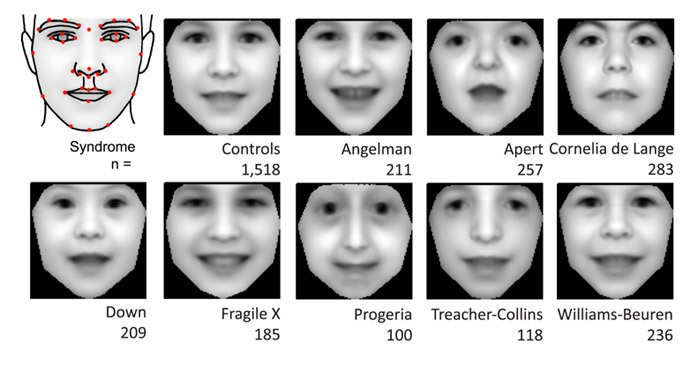

This new software will be looking for similarities with facial structures for various conditions of 91 disorders and return matches ranked by likelihood.

The idea of the Oxford-developed software is based on the assumption that between 30 and 40 percent of rare genetic disorders involve changes in the shape of the face and skull.

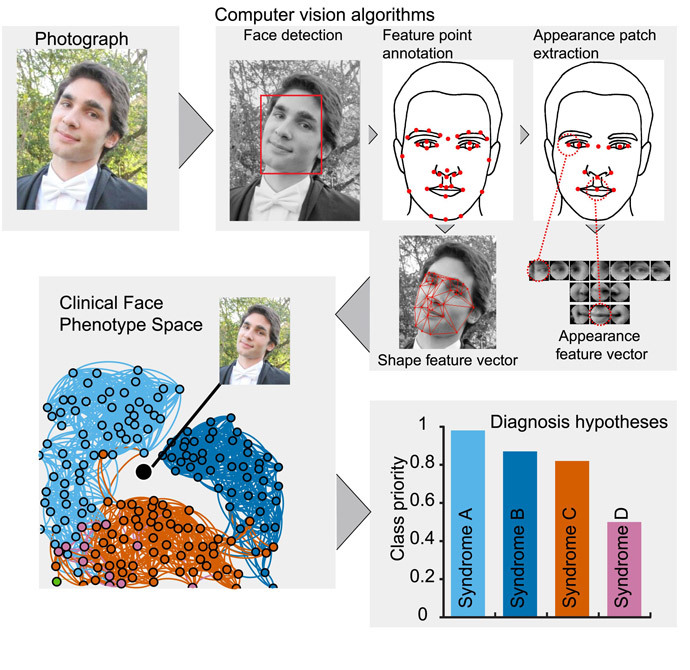

This new algorithm extracts phenotypic information from non-clinical photographs, and, using machine learning, models human facial dysmorphisms in a multidimensional “Clinical Face Phenotype Space,” researchers also explained in the article in the journal eLife Sciences.

"The algorithm increasingly learns what facial features to pay attention to and what to ignore from a growing bank of photographs of people diagnosed with different syndromes," lead researcher Dr. Christoffer Nellaker of the MRC Functional Genomics Unit at the University of Oxford said.

Just like photo software used by Google, Picasa or Facebook, the computer program will be able to recognize faces in ordinary, everyday photographs, an official press-release from the Medical Research Council's Functional Genomics Unit at Oxford University said.

This new software will be looking for similarities with facial structures for various conditions of 91 disorders and return matches ranked by likelihood.

The idea of the Oxford-developed software is based on the assumption that between 30 and 40 percent of rare genetic disorders involve changes in the shape of the face and skull.

This new algorithm extracts phenotypic information from non-clinical photographs, and, using machine learning, models human facial dysmorphisms in a multidimensional “Clinical Face Phenotype Space,” researchers also explained in the article in the journal eLife Sciences.

"The algorithm increasingly learns what facial features to pay attention to and what to ignore from a growing bank of photographs of people diagnosed with different syndromes," lead researcher Dr. Christoffer Nellaker of the MRC Functional Genomics Unit at the University of Oxford said.

This Clinical Face Phenotype Space is resistant to “spurious variations such as lighting, pose, and image quality which would otherwise bias analyses.”

The software will build a description of the face structure by identifying corners of eyes, nose, mouth as well as other features and compares the result against what it has learnt from other photographs loaded into the system’s database.

“A doctor should in future, anywhere in the world, be able to take a smartphone picture of a patient and run the computer analysis to quickly find out which genetic disorder the person might have,” Nellaker said.

The abovementioned “Clinical Face Phenotype Space” allows for automatically clustering patients together by phenotype even when no known syndrome diagnosis exists, thereby aiding disease identification.

It is also possible to cluster cases, where no documented diagnosis exists, which potentially will help in identifying ultra-rare genetic disorders.

Diagnosing a suspected developmental disorder normally requires clinical geneticists’ conclusions given patient’s facial features, follow up tests and their own expertise.

But scientists stressed that of over 7,000 known inherited disorders, only a minority of patients with a suspected developmental disorder received a clinical, let alone a genetic diagnosis.

While such diagnostics can’t replace traditional methods, it may be crucial in starting early treatment of such conditions as Down’s syndrome, Angelman syndrome, or Progeria and providing proper support.

“A diagnosis of a rare genetic disorder can be a very important step. It can provide parents with some certainty and help with genetic counseling on risks for other children or how likely a condition is to be passed on,” Nellaker said.