Stuxnet patient zero: Kaspesky Lab identifies worm’s first victims in Iran

Nearly four years after the notorious worm Stuxnet wreaked havoc on Iranian nuclear centrifuges, Kaspersky Lab has identified patient zero for the world’s “first cyber weapon.”

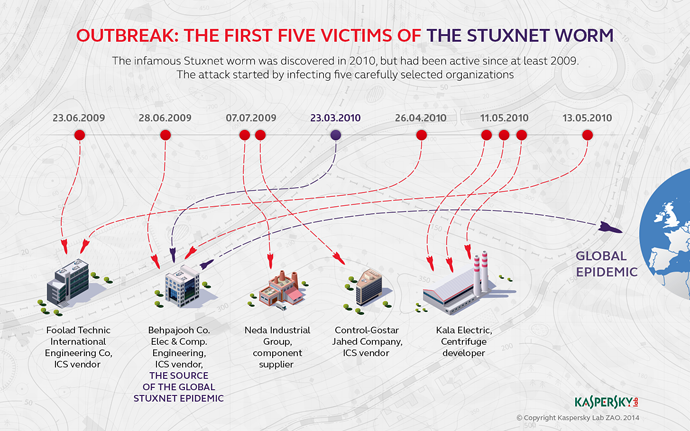

After analyzing more than 2,000 Stuxnet files collected over a two-year period, Kaspersky has revealed the first five victims of the Trojan attack, which was first uncovered in June 2010.

All five of the victims worked within industrial control systems in Iran, and in one way or another, had connections to Iran's nuclear program.

The first two targets – Foolad Technical Engineering Co. and Behpajoah Co. Elec & Comp Engineering – were initially targeted as early as June 2009.

Foolad, which creates automated systems for Iranian industrial facilities, would go on to be struck again in April 2010 – a move which Alex Gostev, chief security expert at Kaspersky Lab, said was no coincidence.

“This persistence on the part of the Stuxnet creators may indicate that they regarded Foolad Technic Engineering Co. not only as one of the shortest paths to the worm's final target, but as an exceptionally interesting object for collecting data on Iran's industry,”he wrote.

The initial version of Stuxnet infected its first computer at Foolad just hours after being created on June 22, 2009. The short interval between creation and infection lead Kaspersky to conclude that the initial infection was not done via USB.

The following month, Neda Industrial Group – which makes products with potential military applications – and Control-Gostar Jahed Company, another Iranian firm operating in industrial automation, were also hit.

According to Gostev, Neda and Gostar were likely employed as intelligence gathering hubs, as the strain of Stuxnet that infected them never spread beyond the companies.

Gostev believes they might have been needed to gain information about Siemens Step7 software, which is used to give instructions to industrial programmable logic controllers (PLCs). A PLC is a digital computer used for the automation of mainly industrial electromechanical processes, including the operation of the centrifuge cascades at uranium enrichment facilities.

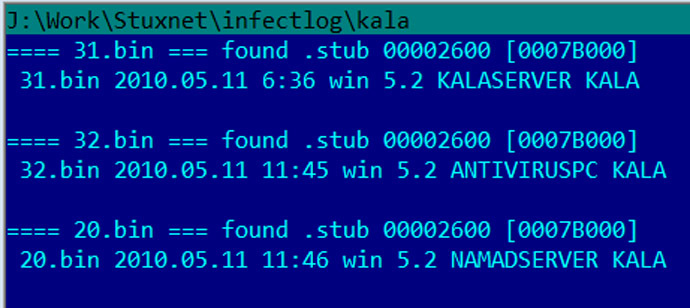

Stuxnet’s primary target was evident in the fifth and last company, Kala Electric, which was hit on May 11, 2010.

According to Kaspersky, Kala was the most “intriguing” organization targeted with the Trojan horse, as it “produces uranium enrichment centrifuges,” among other products for industrial automation.

Why target an outsider

With the nuclear facilities themselves cut off from the outside world, the attacks were conducted under the belief that the firms would exchange information with their clients – especially uranium enrichment facilities in the Islamic Republic – thereby facilitating the assault on Iran’s nuclear program.

“It was absolutely impossible to send the malware directly to the Iranian [uranium enrichment] facility, because, of course, it was not connected to an internet network and there were a lot of protective policies,” Sergei Loshkin, senior anti-virus expert at Kaspesky Lab, told RT.

“So the creators of Stuxnet, they were thinking that these companies would do some communications with power plant workers; maybe exchange with USB devices. That’s probably how Stuxnet infected the system.”

This form of attack is known as supply-chain attack vector, whereby the worm is delivered to the target indirectly through its network of contacts.

A US-Israeli operation?

According to Gostev, the automated control machines employed to operate thousands of spinning uranium enrichment centrifuges at Natanz – which is built eight meters underground and is protected by 2.5 meter thick concrete walls – were set to run at speeds that would ultimately damage them, but not lead them into a catastrophic breakdown.

By September 2010, Israeli media reports said that centrifuge operational capacity at Natanz had dropped by 30 percent. By November 23, 2010, it was announced that uranium enrichment at the plant had halted several times due to serious technical issues.

Many media reports have speculated that Israel and the US were behind Stuxnet. An investigation by The New York Times claimed the US pulled the trigger.

READ MORE:US unleashed Stuxnet cyber war on Iran to appease Israel – report

In July 2013, former National Security Agency (NSA) contractor Edward Snowden also said that Stuxnet was a joint US-Israeli project.

READ MORE:Snowden confirms NSA created Stuxnet with Israeli aid

Despite allegations blaming the US and Israel for the attack, however, neither Kaspersky nor any third party has directly named a culprit in the historical cyber-sabotage operation.

READ MORE:Stuxnet evolution:NSA input turned stealth weapon into internet-roaming spyware

A new book by Kim Zetter, titled 'Countdown to Zero Day,' contains extensive interviews with Kaspersky staff regarding the Stuxnet infection and previously unreleased technical information regarding the attack.