Industrial pollution turning Canadian lakes into ‘jelly’

The Canadian lakes are slowly but steadily turning into jelly since the industrial pollution has given jelly-clad organisms an edge over their calcium-protected competitors, researchers say, warning about potential impact on drinking water systems.

A battle between competing planktons in the delicate Ontario Lakes ecosystems is being won by “jelly-clad organism” called Holopedium that’s got an advantage over the planktonic Daphnia – all thanks to industrial pollution and acid rain – says new research by Cambridge University scientists published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

The population of Holopedium – which has a “jelly” coat that gives them more protection from water predators – have doubled since the 1980s in many of the lakes, scientists behind the study say.

#AcidRain turned #Canadian#lakes into jelly full of #Holopedium & wreaked #ecological havoc. http://t.co/8HJf0tuE5Kpic.twitter.com/a7ZIsTeFQR

— Eric Cai (@chemstateric) November 19, 2014

The dramatic decline in the water calcium levels has left Daphnia without crucial component to develop their exoskeleton defending them from predators. Thus Daphnia populations are declining, leaving more algae for other organisms to feed on, such as jelly-protected Holopedium.

“Lakes across eastern Canada have seen Holopedium populations explode in the last thirty years; particularly in lakes in the province of Ontario that have seen a recent Eurasian invasion of the spiny water flea – which also favours hunting Daphnia, affording Holopedium even more room in these ecosystems to expand,” Cambridge said in a press release.

Scientists warn that the “jellification” of Canada’s lakes will further prevent vital nutrients in the food chain flow and may eventually clog filtration and drinking water systems, as in Ontario, some 20 percent of drinking water comes from lakes with depleted calcium concentrations.

“As calcium declines, the increasing concentrations of jelly in the middle of these lakes will reduce energy and nutrient transport right across the food chain, and will likely impede the withdrawal of lake water for residential, municipal and industrial uses,” said study co-author Dr Andrew Tanentzap, from the University of Cambridge’s Department of Plant Sciences.

'Daphnia Family' by Karl Gaff, winner 2014 UCD Images of Research Competition @UCD_Research@ucdscience@UCDSciExpic.twitter.com/4zhaGSSZnu

— UCD Innovation (@UCDinnovation) September 26, 2014

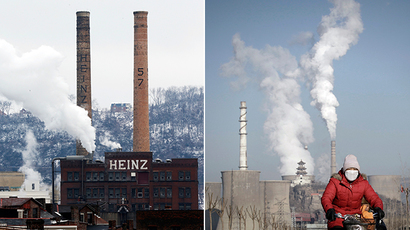

Tanentzap says that industrialization in northern hemisphere deposited a lot of acid that displaced calcium from soil that feed these lakes.

“Pollution control may have stopped acid deposits in the landscape, but it’s only now that we are discovering the damage wasn’t entirely reversed,” he says.

Besides Calcium loss, scientists also suggest that climate change is causing depletion of oxygen in the lakes that could lead to increasing populations of “larval midges – the main predator of Daphnia.”

“It may take thousands of years to return to historic lake water calcium concentrations solely from natural weathering of surrounding watersheds,” Tanentzap warned. “In the meanwhile, while we’ve stopped acid rain and improved the pH of many of these lakes, we cannot claim complete recovery from acidification. Instead, we many have pushed these lakes into an entirely new ecological state.”