Mass extinction for Earth’s oceans probable, comprehensive study says

Published 17 Jan, 2015 10:19 | Updated 17 Jan, 2015 10:18

The first comprehensive study of its kind has determined that ocean life is facing mass extinction from human activity. But the record damage is still reversible – unlike our impact on land. American scientists say the effects can be mitigated.

We’ve known for a while that achieving sustainability would be impossible with our lifestyles. Although the majority of Earth is covered in water we are vastly reliant on, many of our practices are causing unprecedented damage to marine biology: coral reef damage, resource mining, fish farming, construction work, chemical pollution, the depletion of bio resources, unintended species migration, global warming, military drills – to name just a few.

The picture has just been made clearer by a study that for the first time ever brought all these strands together. Drs. Malin L. Pinsky, Stephen R. Palumbi, Douglas J. McCauley and colleagues from the University of California have dug into hundreds of sources past and present, including the fossil record and statistics on shipping and seabed mining to form the chilling conclusions of their study, published Thursday in the journal Science.

“We may be sitting on a precipice of a major extinction event,” McCauley says on the analysis, which has already received wide acclaim from marine biologists and experts in related fields.

READ MORE: First time in 2 mn years, melting Arctic ice threatens mass-scale species contamination

“If by the end of the century we’re not off the business-as-usual curve we are now, I honestly feel there’s not much hope for normal ecosystems in the ocean,” Palumbi said.

READ MORE: Melting of Antarctic ice sheet and 3-meter sea level rise inevitable - study

One of the key conclusions is that the oceans had until now largely evaded the damage we had caused to terrestrial life, seeing as we’re after all a terrestrial species. But after 1800, when industrialization hit, land extinction sped up and the stage was set for irreversible water damage, which is now mirroring the situation.

“Current trends in ocean use suggest that habitat destruction is likely to become an increasingly dominant threat to ocean wildlife over the next 150 years,” the team said in their study. And because oceans are a fluid mechanism, and much more difficult to monitor accurately than land, there is practically no way of reaching a conclusion on the average state of Earth’s water. Some places could be far wars off than others, hence the importance of the new cumulative analysis.

READ MORE: Big US banks balk at funding Great Barrier Reef coal port

READ MORE: Danger to food chain? Microplastic contaminates found in Sydney Harbor

We’re squeezing the species on all sides: mangrove farming destroys habitats, while our fish nets have affected 20 million square miles of ocean already, altering the continental shelf.

Seabed mining contracts are an especially huge change: the area went from zero square miles in the year 2000 to a staggering 460,000 in 2014. This serious threat is especially dangerous to sensitive and unique ecosystems.

And while we no longer hunt whales to the same extent, their lives are now affected by a rapidly growing number of shipping lanes.

READ MORE: US Navy to kill, injure ‘thousands’ of whales, dolphins during drills – activists

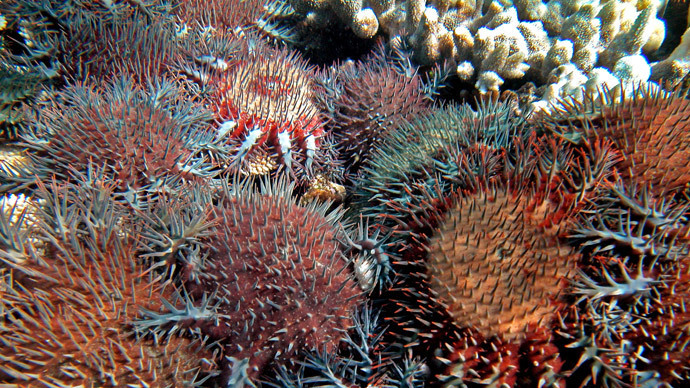

The process is also a chain. The human footprint has caused a 40 percent decline in coral reefs worldwide, which consequently leads to habitat destruction for marine species. Some migration may result in the arrival of predatory species to ecosystems that are not prepared to accept them, and so on. But everyone is feeling the impact.

“If you cranked up the aquarium heater and dumped some acid in the water, your fish would not be very happy,” Pinsky said. “In effect, that’s what we’re doing to the oceans.”

And it starts on land for many marine animals: some lay eggs – like sea turtles; seabirds nest in cliffs, and so on. Some have already become extinct due to our land activity.

READ MORE: Nicaragua starts work on $50bn canal between two oceans

“But in the meantime, we do have a chance to do what we can. We have a couple decades more than we thought we had, so let’s please not waste it,” Palumbi said. "I fervently believe that our best partner in saving the ocean is the ocean itself.”

READ MORE: BP caps cash pipeline to research worst oil spill in US history

McCauley elaborates that if we limit the industrialization of Earth’s water, we could facilitate species recovery – much more so than we ever could on land, where the damage is now irreversible in places.

“There are a lot of tools we can use,” he said. The team believes that designing an approach with climate change in mind would be the way to go. It’s about considering how and where species can escape rising temperatures and a lowering of pH levels. As we learn that some areas are indeed affected more gravely than others, one of the approaches may be to limit industrial operations to some areas, while allowing others to recover.

“It’s creating a hopscotch pattern up and down the coasts to help these species adapt,” Pinsky said.