Mars’ vast glacier belts could cover planet with 1 meter of ice – study

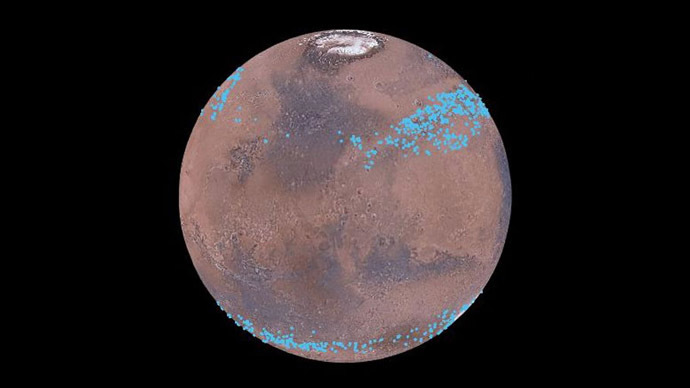

Mars has been known to host water. Now, for the first time, scientists have measured the territory of its glaciers, which crisscross the planet, hiding beneath layers of dust. It’s enough to cover the whole of the Red Planet in a meter of ice.

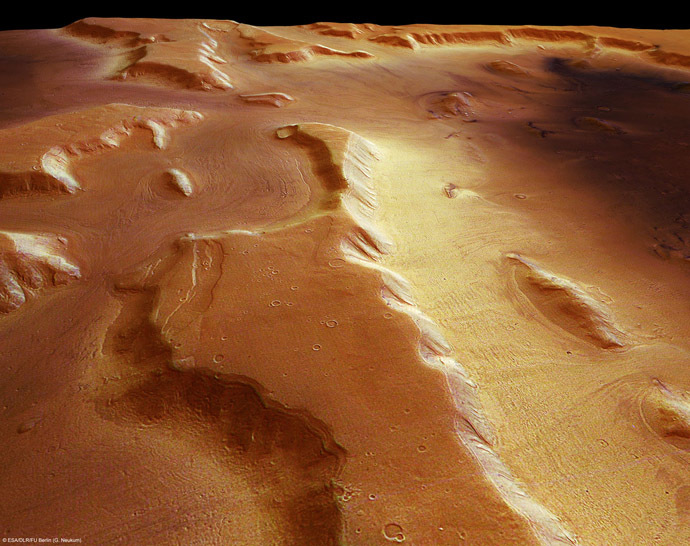

The findings, published in Volume 41 of the journal Geophysical Research Letters, build on previous knowledge – the scars left by the water that used to flow on the Red Planet millions of years ago, the presence of polar ice caps, as well as chemical elements that tell a story. Underneath all that, however, lay vast expanses of frozen water invisible from space.

Or rather, they were only slightly visible with our satellites. But science didn’t know if they were made of frozen H2O or CO2, carbon monoxide.

Then, NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter made the call: it was water ice after all. Next up was determining its thickness, or whether the glaciers resembled anything we were used to on Earth.

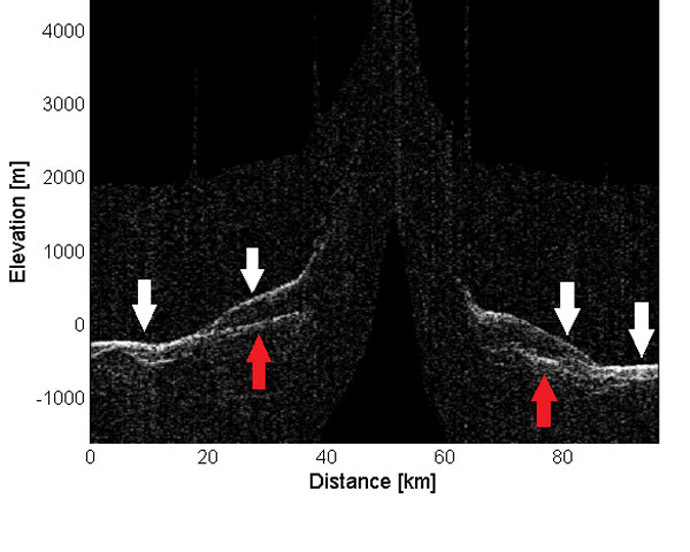

A Copenhagen-based team at Nils Bohr Institute proposed a formula to surmise the above. It employs existing models of ice flow projections, combined with what we could see from space. The two approaches combined allow for the eventual calculation of the volume of ice in the glaciers.

"We have looked at radar measurements spanning 10 years back in time to see how thick the ice is and how it behaves. A glacier is after all a big chunk of ice and it flows and gets a form that tells us something about how soft it is. We then compared this with how glaciers on Earth behave and from that we have been able to make models for the ice flow," said Nanna Bjornholt Karlsson, of the Nils Bohr Institute’s Center of Ice and Climate.

"We have calculated that the ice in the glaciers is equivalent to over 150 billion cubic meters of ice – that much ice could cover the entire surface of Mars with 1.1 meters of ice,” Karlsson said. “The ice at the mid-latitudes is therefore an important part of Mars' water reservoir."

The researchers believe there is a reason the ice does not simply evaporate into space, the way water that is not frozen would, owing to Mars’s low pressure. Unlike the water, the ice is held down by the dust layering.

These calculations are just the latest in a series of ever more frequent astronomic discoveries. Mars has been catapulted into the space headlines thanks to the work done by the Curiosity rover. NASA aims to put humans on the planet by 2030 and we need to know as much as possible now about what resources are available to us on the Red Planet, aside from our mission to find traces of life there.

One other recent discovery centered on deposits of “fixed” nitrogen and molecules containing carbon, both central to creating life as we know it.