Russian rocket engine export ban could halt US space program

Russia’s Security Council is reportedly considering a ban on supplying the US with powerful RD-180 rocket engines for military communications satellites as Russia focuses on building its own new space launch center, Vostochny, in the Far East.

A ban on the rockets supply to the US heavy booster, Atlas V, which delivers weighty military communications satellites and deep space exploration vehicles into orbit, could impact NASA’s space programs – not just military satellite launches.

An unnamed representative of Russia’s Federal Space Agency told

the Izvestia newspaper that the Security Council is reconsidering

the role of Russia’s space industry in the American space

exploration program, particularly the 2012 contract to deliver

the US heavy-duty RD-180 rocket engines.

Previously, Moscow has not objected to the fact that America’s Atlas V boosters, rigged with Russian rocket engines, deliver advanced space armament systems into orbit. If a ban were to be put in place, however, engine delivery to the US would probably stop altogether, beginning in 2015.

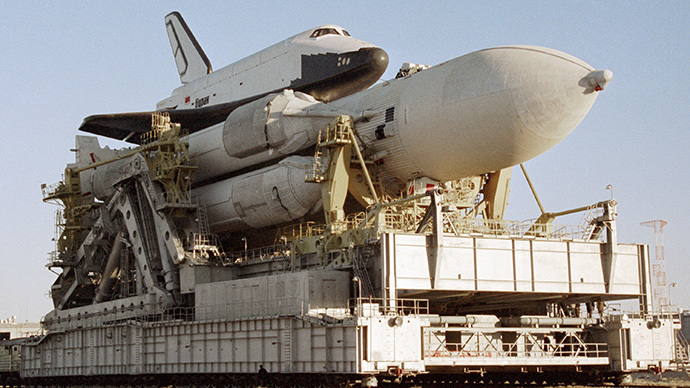

Over the last decade, most of NASA’s Atlas V heavy rocket launches performed by the United Launch Alliance (a Boeing/Lockheed Martin joint venture) were carried out using Russian RD-180 dual-nozzle rocket engines, a legacy of the Soviet Buran space shuttle program and its unparalleled rocket booster Energia, which could put 100 tons worth of spacecraft or satellite payloads into orbit.

Military payloads

It is widely believed that many Atlas V launches carry a military payload. Such Lockheed Martin-designed military spacecraft include the Advanced Extremely High Frequency (AEHF) series of communications satellites launched for Air Force Space Command, the mysterious Palladium at Night communication platform designed for the US Navy’s Ultra-High Frequency (UFO) Follow-On program, and most certainly all three launches of Boeing’s X-37 unmanned demonstrator spacecraft. These are only a part of the military space missions undertaken by Atlas V rockets, boosted by RD-180 engines

A ban could also affect the US’s non-military space exploration launches, which are also highly dependant on the Atlas V rocket and RD-180 engines. The most famous and challenging among these exploration missions are NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, now traveling to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt (launched in 2006), and the Curiosity Mars rover (launched in 2011) currently operating on the Red Planet.

A number of experts told Izvestia that termination of the rocket engine contract would not be a good idea commercially for NPO Energomash, which produces the rockets, as at the moment it exclusively makes RD-180 engines for the US space industry. The rockets typically take Energomash 16 months to produce.

If production of the RD-180 engine is halted, the enterprise would have to find other contracts to keep its production line and experienced staff busy.

“In my opinion, stopping the export of rocket engines to the US is stupid, as we would suffer financial and reputational losses,” Ivan Moiseyev, scientific head of the Space Policy Institute, told Izvestia. “The US would not suffer much and would definitely continue with military space launches, while Russia would have to stop production of the RD-180, because no one else needs the RD-180 engine.”

Many space experts believe that the US would find it difficult to quickly replace the Russian-made rocket boosters.

Meanwhile, Energomash could soon find other orders elsewhere.

Russia plans to start space launches from its new,

multibillion-dollar Vostochny cosmodrome in the Far East in 2015.

Vostochny will host a heavy rocket class launch pad, which means

the producer of world’s most powerful rocket engines will be kept

busy for many years to come.

The RD-180 is equivalent to half of the Soviet-era Energia booster, the most powerful liquid rocket engine ever made. With 20 million horsepower output, the Soviet-era RD-170 was about 5 percent more powerful, yet 1.5 times smaller, than American’s F-1 first stage rocket engine made for the Saturn V booster of the Apollo lunar program.

Reportedly, when the Energia booster with the Buran space shuttle

was launched in November 1988, the massive concrete bays paving

the Baikonur cosmodrome in Kazakhstan were flying around like dry

leaves, due to the immense power coming from the four RD-170

engines, which blasted the 2,400-ton rocket booster into

space.

In the post-Soviet era, Russian-US rocket engine cooperation

started back in 1996, when America’s General Dynamics Company

bought exclusive rights for use of RD-180 in the US, later

selling it to Lockheed Martin for its Atlas rocket program. NPO

Energomash, the producer of unique engines based in Moscow’s

suburb Khimki, signed a contract for production of 50 RD-180

engines and an option for the production of another 51 units.

A specially created joint venture, RD-AMROSS, between NPO

Energomash and Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne, has already

delivered 63 engines to the US worth $11-15 million apiece,

reportedly 40 of them have already been used. In December 2012, a

new contract was signed to deliver another 31 engines. But this

contract is now being reconsidered by Russia’s Security Council,

according to Izvestia.

Rocket engines: space at stake

The RD-AMROSS joint venture has always been controversial for Russia’s military.

In 2011 Russia’s Audit Chamber announced that the RD-180 rocket engines delivered to the US according to the 1996 contract were sold for only half of their real production value. The total loss in 2008-09 reached 880 million rubles (about $30 million) or 68 percent of all financial losses of NPO Energomash at the time, the Audit Chamber said.

In an interview, the general director of RKK Energia Corporation,

Vitaly Lopota, estimated that at the time of the RD-180 first

launch in the late 1980s, USSR was “at least” 50 years ahead of

America’s liquid fuel rocket engine technology.

In the 1990s Russia agreed not only to sell unique engines to the US, but also provided the Americans with full documentation on the engine’s design specifications. But the US space industry opted to buy ready engines instead of trying to make them on their own, because of the technological and material engineering gap between the two countries’ space industries. And today, the situation appears to be pretty much the same.

In December 2012, the head of Roskosmos, the Russian Federal Space Agency, Vladimir Popovkin, commented to Izvestia on the engines: “Americans are buying RD-180 engines and are negotiating to buy promising new RD-193 engines, because they’ve learned that we’re making a quality product, the best liquid-fueled rocket engines in the world. For them it’s easier to buy than to make up with us, [while] for us it is important to ensure the development of the NPO Energomash enterprise.”

In June 2013, the US Federal Trade Commission launched an

antitrust investigation into United Launch Alliance, which was

accused of “monopolizing” the rocket engine market and thus

barring its direct rival, Orbital Sciences Corporation, from

obtaining RD-180 engines for its Antares rocket booster to break

into the lucrative market for US government rocket launches.

Experts say that the fact that Orbital Sciences Corporation is battling for the RD-180 could only mean that the company has so far failed to acquire anything similar on either the American, or the international space industry market.

Orbital Sciences’ Antares rocket is powered by Aerojet AJ-26 engines, which are actually Soviet NK-33 engines produced for the super-heavy N-1 rocket booster of USSR lunar program. Orbital Sciences once managed to buy 43 NK-33 engines stored for decades in Russian space corporation’s depots, and then adopted them for their needs. Now Orbital Sciences would like to restart production of the NK-33, but Energomash announced that this engine is out of production for the time being. In this situation, Orbital Sciences is taking ULA to court for the right to buy Russia’s RD-180 rocket engines.

SpaceNews reported earlier this month that NASA’s internal agency

audit is warning that the Orion deep-space manned spacecraft

program faces a “difficult budget environment” that ultimately

could cause delays and cost increases. The Orion capsule could be

launched with various rockets, including ULA’s Atlas V and Space

Exploration Technologies’ Falcon 9.

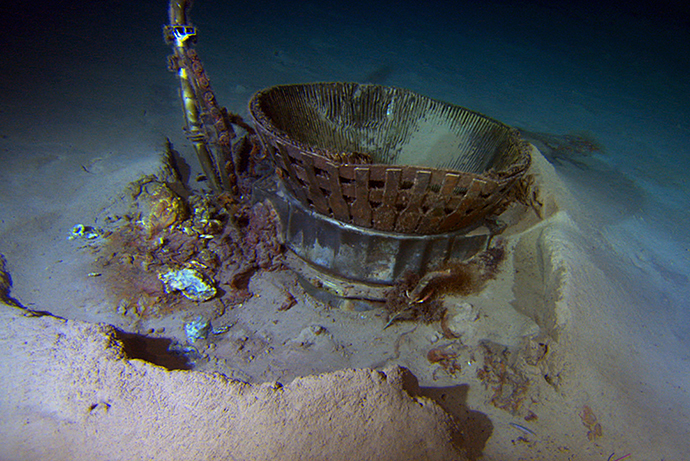

In spring of this year, Amazon founder and space enthusiast Jeff

Bezos, owner of the Blue Origin space exploration startup,

financed a successful expedition recovering two F-1 engines for

Apollo project’s Saturn V rocket from the Atlantic sea bed near

Florida’s Kennedy Space Center. Bezos said that his fascination

with space began back in 1969 with the Apollo program, when he

saw astronaut Neil Armstrong walk on the Moon.

The rocket engines still remain property of NASA and the US government, and Bezos has promised NASA the units to place them on display at a museum in Seattle as “testament to the Apollo program.”