Apocalyptic supervolcanoes can suddenly explode ‘with no outside cause’

Scientists have discovered what causes cataclysm-inducing supervolcanoes to erupt, and the answer offers little reassurance. Their eruptions are caused by magma buoyancy, which makes them less predictable and more frequent than previously thought.

A team of geologists from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETH) modeled a supervolcano – such as Yellowstone in Wyoming – using synthetic magma heated up with a high-energy X-ray to see what could create a powerful discharge. A separate international team, led by Luca Caricchi of the University of Geneva, conducted more than 1.2 million computer simulations of eruptions.

Both groups have arrived at similar conclusions, with twostudies simultaneously published in Nature Geoscience magazine.

"We knew the clock was ticking but we didn't know how fast: what would it take to trigger a super-eruption?” said Wim Malfait, the lead author of the ETH study.

"Now we know you don't need any extra factor - a supervolcano can erupt due to its enormous size alone.”

It was previously thought that supervolcanoes – which spew out hundreds more times of lava and ash than ordinary ruptures – could be triggered by earthquakes or other outside tectonic phenomena.

It was also clear that these volcanoes do not operate like ordinary eruptions, which rely on magma filling their chambers, and spurting through an opening, once the pressure gets to a certain point, since the chambers of supervolcanoes are too large to be over pressurized to the same degree.

Now, the studies have identified the unique supervolcano mechanism that makes their discharge more like powerful explosions than normal eruptions.

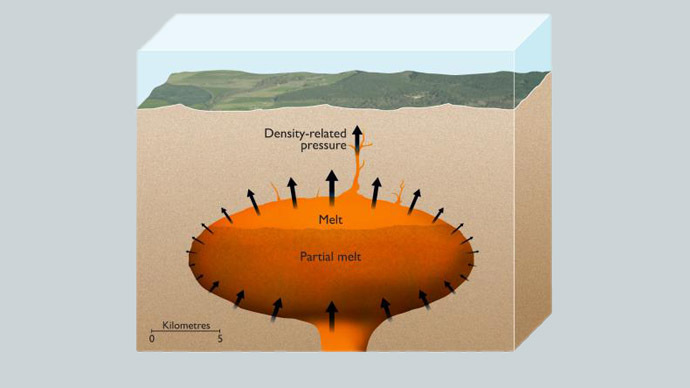

The molten magma in the mostly underground supervolcano is lighter than the surrounding rocks, and the difference in pressure, creates a 'buoyancy effect', meaning the super-hot terrestrial soup is always attempting to burst out.

“The difference in density between the molten magma in the caldera and the surrounding rock is big enough to drive the magma from the chamber to the surface,” said Jean-Philippe Perrillat of the National Centre for Scientific Research in Grenoble, where the experiments were conducted.

“The effect is like the extra buoyancy of a football when it is filled with air underwater, which forces it to the surface because of the denser water around it. If the volume of magma is big enough, it should come to the surface and explode like a champagne bottle being uncorked.”

The researchers believe that the pressure force of the molten magma pools can be strong enough to crack 10 km thick layers of rock, before spewing out a maximum of between 3,500 and 7,000 cubic kilometers of lava. In comparison, the notorious Krakatoa explosion in 1883 likely ejected less than 30 cubic kilometers of debris into the atmosphere.

The effects on Earth are likely to be fundamental, with previous studies suggesting that such a supervolcano could decrease the temperature on Earth by 10 C for a decade, as the ash would prevent sunlight from reaching the ground.

The last supervolcano eruption in Lake Toba took place more than 70,000 years ago. According to one highly-contested theory it may have wiped out more than half of the planet’s population; in any case the effect on the world would be dramatic.

"This is something that, as a species, we will eventually have to deal with. It will happen in future," said Dr Malfait.

"You could compare it to an asteroid impact - the risk at any given time is small, but when it happens the consequences will be catastrophic."

A volcano has to eject more than 1,000 cubic km of debris in a single eruption to be counted as a supervolcano, and there are less than ten potential sites with sufficiently large magma chambers around the world, though there may be others lurking underneath the ocean surface. These formations, which are more often flat with no outlet, are expected to erupt once every 50,000 years, though there is no regularity to the frequency of eruptions.

The computer modelers believe that the buoyancy mechanism means that such eruptions occur more frequently than previously thought, though the exact extent is hard to estimate without studying magma flows at each potential location.

Nonetheless, the ETH scientists say that there could be detectable pressure changes, and perhaps even spectacular rises of ground level sometime before the eventual explosion. But it is not clear how long after such changes an eruption would take place, or whether advance knowledge would actually help to mitigate its impact.