Purgatory of Melilla: African immigrants’ hard road to Europe

Mamadou sits on a rock, his eyes turned towards the sea, the hood on his head to protect him from the wind. Here on mount Gurugu, the wind blows all day long.

He is 17 years old and comes from Mali, and since two months ago he has been one of about 4,000 inhabitants of what is a veritable tent city on the slopes of an impervious mountain, exposed to every kind of hardship. Tents made of plastic bags and branches, blankets retrieved from garbage cans, small bonfires to keep warm, and nothing more. There’s no water on Gurugu.

Fleeing from war, poverty, violence and starvation, Mamadou had crossed Mauritania and Algeria before reaching this mountain that stands behind the Moroccan city of Nador and overlooking the Spanish enclave of Melilla, Europe’s back door to Africa.

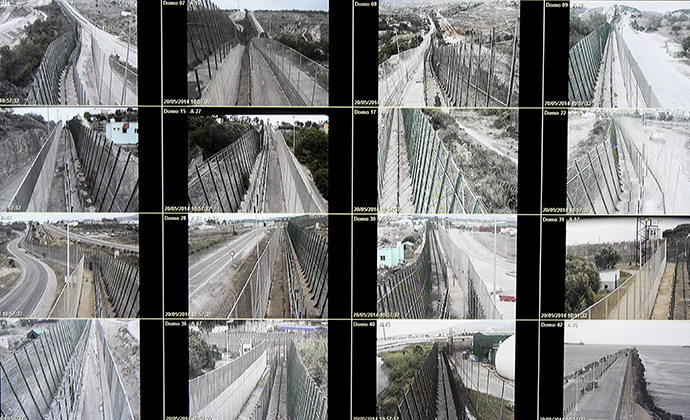

This is a real village nestling among the trees and clouds, a sea of makeshift tents, packed with migrants from nearly every corner of Sub Saharan Africa. There are Malians, Senegalese, Nigerians, Cameroonians, Liberians, Ghanaians, and all have arrived on Gurugu with a single goal: to jump the wall that divides Morocco from Melilla. It is a triple barrier 12km long, controlled by dozens of cameras and continuous patrols both by the Moroccan police and the Spanish Guardia Civil, a seemingly impregnable fortress, but not for these people, on the run from a harsh life who are dreaming of a better future.

Three or four times a week migrants living on Gurugu descend the mountain in waves, trying to climb over the fence and reach Europe. Those who make it end up at the CETI (Centro de Estancia Temporal de Inmigrantes), a first aid center on the verge of exploding with over 2,000 people, crammed into a space conceived for 480, waiting to know their fate. The others are hunted down by the Guardia Civil and returned immediately to Morocco where they are left in the hands of the Moroccan soldiers.

“A clear violation of international law,” explains José Palazon, an activist from Melilla, “that exposes migrants to violence in a country that doesn’t respect human rights. Whenever there is an attempt to jump the wall hundreds of migrants are injured, not by the iron fences, but from the gun barrels of the Moroccan police.”

Indeed the Moroccan police are the greatest nightmare for the migrants: both for those dwelling on Gurugu and for the others hiding in the forests and in the suburbs of Moroccan cities, all waiting to reach Europe (about 80,000 people according to a rough estimate).

“Almost every day, at dawn, the Moroccan soldiers leave their base at the foot of Gurugu, come to our camp and destroy everything” says Idriss, who can barely walk after being severely beaten. “They pull down the tents, set fire to them, throw away the food, steal the little money we have, our phones. And if they can catch anyone then they arrest him and beat him, and then take him to Rabat [the capital]. We fall over the cliffs, many of us fracture arms and legs, we are hurt and we have no medicine to treat us. Over the years we have stopped counting the dead.”

Mamadou bears the signs of his last beating on his left forearm, a large wound that has recently healed. Cold, hunger, disease and violence are the order of the day on Gurugu. A mountain that looks like one of Dante’s circles of hell, where only three or four girls have the courage to live instead of joining the women and children hidden in the woods near Selouane, at the foot of the other side of the mountain, who are waiting to board a small boat and reach Melilla’s beach.

Not all migrants, in fact, try to enter Melilla by jumping the wall. Those who do so are the most desperate, the ones who have spent all the money they had for the trip, money that was stolen by the police, by the mafia mobs that control the smuggling of migrants. Those who can afford to try to pass by sea, or by buying false passports, as Syrians do. Others pay 2,000 euro for a car ride. Not in the passenger seat, but In the false bottom of a car, near the engine, near the exhaust pipe.

“A huge risk, these people remain without air and in a high temperature for hours,” explains Juan Antonio Martin Rivera, a lieutenant of the Guardia Civil. “As far as we know, it is only here that migrants are trying to cross the border in this way.”

All migrants have a dream: Europe. A Europe which, however, doesn’t want them, and turns a blind eye to the – both Moroccan and Spanish – violence as many NGOs point out. It was only two months ago that the Civil Guard, under pressure from NGO associations and the press decided to abandon the rubber bullets that over the years have seriously injured hundreds of migrants.

According to Abdelmalik El Barkawi, delegate of the Spanish Government in Melilla, “The enclave is facing an unprecedented migratory pressure.”

Perhaps this is why the government of Mariano Rajoy has said nothing about the new barrier that the Moroccan government has begun building around Melilla. A new barrier with barbed wire that, “according to Spanish newspapers has been financed with part of the 50 million euro that Spain asked from the EU to strengthen its borders. These reports were first confirmed and then denied by the government in Madrid,” states Jesuit priest Esteban Velazquez, who is among the few to provide assistance to migrants on the Moroccan side.

Left to themselves, trapped at the gates of Europe, and helpless victims of ongoing violence, sub-Saharan migrants “have to face illegal deportations by Spain. When a migrant is able to pass the first barrier he is formally in Spanish territory and therefore can’t be brought back to Morocco. He has the right to have a lawyer and a translator, he can apply for asylum and can’t be deported to a country where his life is endangered,” states Tereza Vazquez Del Rey, lawyer at CEAR (Comision Espanola de Ayuda al Refugiado).

A hundred kilometers from Nador and Melilla is the city of Oujda, a transit area for many migrants on the Algerian border. Here, life for sub-Saharan Africans appears to have improved since September 2013, when the Moroccan government decided to move migrants arrested in Nador to Rabat rather than to Oujda.

“Previously violence by the police used to be daily,” says Abdullah, 35, from Burkina Faso. “Many people are starting to realize, after several failed attempts, that going to Europe is really too dangerous and that it is not worth risking your life. So a hundred of us have applied for a residence permit in Morocco, we want to try to live and work here.”

The majority of the migrants in Oujda live at the FAC, a small sort of camp made up of tents set up in the Mohamed I University. They are helped by the students and the climate is quite calm. However journalists are not welcome here as there is a strong presence of the Nigerian mafia that controls the smuggling of migrants and women.

So why is the situation for migrants so different between Oujda and Nador? Father Esteban has no doubt: “Because in Nador, and in nearby Beni Ensar, there is the frontier and the Spanish government has delegated the role of the sheriff to the Moroccan police.”

Violence, mafia, arrests, nothing seems to be able to blunt the will power of these people, of these migrants who have been through five years of their lives hiding in Morocco and trying to pass the wall of Melilla.

“A friend of mine, Moussa, was here on Gurugu for five years, and has tried 67 times to jump over the wall,” Ibrahim tells me while playing cards in a tent used as a casino on the slopes of Gurugu. “The 68th he made it. They can treat us like animals, beat us, steal everything from us, hurt us, even kill us, but they don’t know what we are running away from and they don’t know how strong our desire is to reach Europe. Everyone here dreams of having a pair of wings, but if God wills, sooner or later, even without them we will make it.”

Tomaso Clavarino for RT

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.