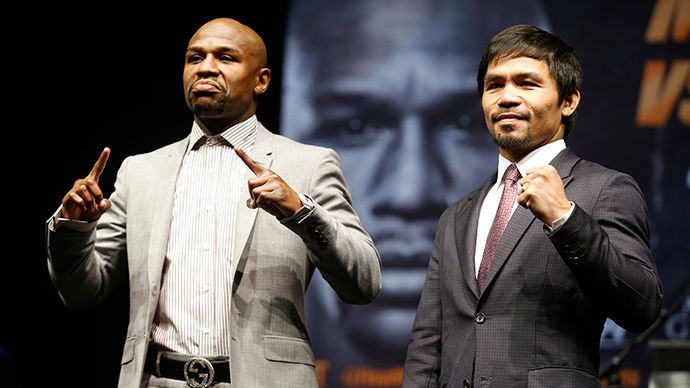

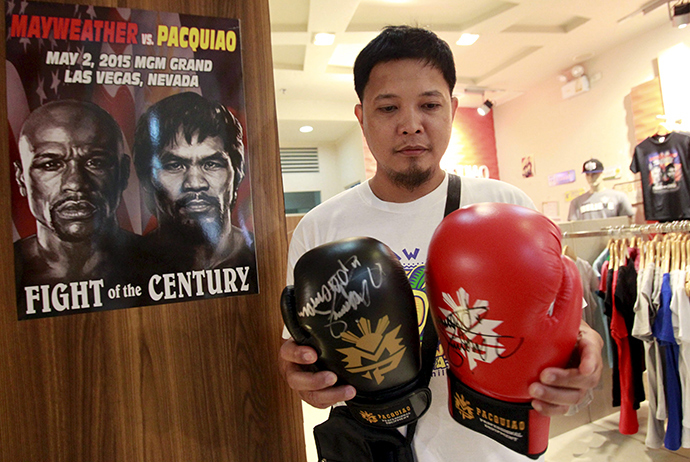

Mayweather vs. Pacquiao, the most lucrative fight ever, but is it the biggest?

The fight on May 2 between Floyd Mayweather Jr. and Manny Pacquiao is one that boxing fans and writers have sought more than any other in recent years, even though both fighters have passed their respective peaks.

But no matter the occasion remains massive, what with Mayweather’s status as the highest earning athlete in sport, the fact he is only two fights away from matching Rocky Marciano’s 49-fight unbeaten record, and the veneration accorded Pacquiao as a national hero in the Philippines. Then there is the bad blood that exists between Pacquiao’s trainer, the widely respected Freddie Roach, and Mayweather’s father Floyd Mayweather Snr., who will be in his son’s corner.

Some of the hype surrounding the fight has gone as far as laying claim to it being the biggest in the history of boxing. While, yes, the projected $300 million the fight will generate undoubtedly qualifies it as the most lucrative fight there’s ever been in boxing, in terms of its wider significance and impact, it pales in comparison to some of the classic fights of the past.

Consider, for example, the Jack Johnson vs. Jim Jeffries heavyweight title fight of 1910, held at a specially built outdoor arena in Reno, Nevada. At stake was more than prize money. At stake was racial pride in an age when blacks in America were being lynched on a regular basis in the South and in the North were regarded as second-class citizens.

Jeffries was tempted out of retirement by a press and boxing establishment desperate to regain the heavyweight title for the ‘white race’. When the former champion finally agreed to face Johnson, and the fight was made, racism flowed like a river of sewage. Jim Jeffries was the first of many white heavyweights in boxing history to be held up as the ‘Great White Hope’, a title created by the writer Jack London.

Purportedly a socialist, London was a man for whom Darwin’s theory of survival of the fittest applied to humanity, which through the distorted prism of race evidenced the superiority of the white race over every other.

But Jack London and others of his ilk were given cause to think again, as Johnson proceeded to use Jeffries as a glorified punchbag over 15 punishing rounds, when Jeffries was knocked to the canvas for the umpteenth time and couldn’t get up.

In 1936 and 1938 Joe Louis, the “Brown Bomber,” fought Germany’s Max Schmeling in two huge fights over which the poison of racism was again prominent. Hitler and the Nazis were in power in Germany and Schmeling was cast in the role of champion of the Aryan ‘master race’.

In the context of pre-second world war 1930s, with the rise of fascism throughout Europe and its increasing traction in the US, both fights were far more than mere heavyweight boxing bouts. They were pregnant with symbolism and political importance.

Louis lost the first and won the second fight against Schmeling, with whom he later forged a close friendship.

But his victory for ‘democracy’ was also suffused with irony given the prevalence of racism within the United States itself. Louis, like Johnson, was a hero within black communities throughout America, illustrated in the account of the last words of a black death row inmate as he was about to be gassed to death: “Save me Joe Louis! Save me Joe Louis!”

Emile Griffith was the first and remains the only gay world champion there’s ever been in boxing. When he fought Cuba’s Benny Paret in a welterweight world title bout in 1962, Paret turned it into an ugly affair, taking every opportunity to ridicule and abuse Griffith with homophobic slurs. The resulting fight was one of the most cruel ever fought, with Griffith handing his opponent such a beating he never regained consciousness and died ten days later. It was a brutal contradiction of dominant cultural values in which homosexuality and masculinity were considered antithetical and masculinity and violence deemed two sides of the same coin.

Finally, who can argue with the historical importance of a young and precocious Cassius Clay’s defeat of Sonny Liston in 1964 in Miami to claim the world heavyweight title. The 22-year-old Clay was poetry in motion as he slipped and eluded the fearsome Liston’s heavy hands, dancing and moving around the ring like a fast middleweight.

Upon Liston failing to come off his stool at the start of the seventh round, Clay went nuts, taunting the writers and journalists present, who almost to a man had favored Liston, with the cry: “I shook up the world! I shook up the world!” His words proved prophetic, as it was after this fight that he announced his membership of the Nation of Islam and informed the press that he no longer would he be known by the “slave name” Cassius Clay. It was the start of the legend of Muhammad Ali and sitting ringside watching the legend hatch was Malcolm X, Ali’s confidante and adviser just prior to his own very public split from the Nation and its leader Elijah Muhammad.

So while the Mayweather v Pacquiao fight is a huge fight, and comfortably the biggest of recent times, it possesses none of the political, social or historical significance of the aforementioned fights that have gone before and nor should it claim to.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.