Elections in Mali: Francophile A vs. francophile B

While many citizens long for stability as Mali holds its first presidential elections since the 2012 coup, France and others are positioning themselves to reap the rewards of military intervention from the impoverished resource-rich nation.

As one of the world’s poorest countries, day-to-day life in Mali has never been easy for the vast majority of the people, but the situation has significantly deteriorated since the March 2012 military-coup that deposed democratically elected President Amadou Toumani Touré just weeks before scheduled elections. The borders of Mali, once known as "French Sudan," are based on boundaries drawn by French colonists who took little notice of the ethnic homogeneity of the groups living within the lines they drew across the map, the ramifications of which still create deep-seated tribal and ethnic conflicts across Africa today. Mali is defined socially as well as economically between the fertile south where the capital Bamako is located, and an arid neglected north where ethnic Tuaregs have long sought autonomy. The coup’s main protagonist, Captain Amadou Sanogo, had been handpicked by the Pentagon to participate in an international military education and training program sponsored by the US State Department.

After several stints in the United States undertaking military education, Sanogo returned to Mali and staged the coup, which he justified by accusing President Touré’s regime of being complacent and unable to quell the latest Tuareg rebellion in the north. The EU and US, along with international institutions like the World Bank, immediately cut aid and slapped sanctions on the desperately poor import-reliant nation, which only exacerbated disorder and war-like conditions, making any advance against the Islamists impossible. Despite its impoverishment, Mali is an Eldorado of sorts, boasting massive gold reserves, uranium deposits, as well as diamonds and oil. The outrage over the coup displayed in European capitals had more to do with Touré being a Francophile, and a guarantor of stability for foreign multinationals, despite his democratic credentials. Many in Bamako empathized with Sanogo’s position and supported the coup; people were even seen in the streets of Bamako with placards bearing slogans like “Down with the International Community” in the wake of the economic embargo being imposed.

NATO-supplied arms bleed south

Sanogo’s men were hopelessly disorganized, and the disorder and shortage created by Western sanctions led to a power vacuum in the north, which separatists refer to as ‘Azawad’. Hardline Islamists filled the void and asserted their control over northern Mali, and were significantly aided by both the flood of arms supplied by NATO to al-Qaeda affiliated rebels in Libya, and Gaddafi’s looted weapon caches. Reports on the ground confirmed that armed Malian and Nigerien ethnic-Tuareg fighters were seen descending into the Sahara in army issue Toyota Hi-Lux technical trucks used by foreign-funded Libyan rebels – the resurgence of their activity was greatly enhanced by gifts from the Obama administration, such as mortars, machine guns, anti-tank and anti-aircraft weapons originally given to the radical Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG). The main groups active in the north are the secular National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (NMLA) on one side, and hardliners such as Ansar Dine on the other. Both groups briefly partnered after the coup, but collaboration was short-lived. Iyad Ag Ghaly, a prominent Salafi figure who led previous Tuareg uprisings and spent time as a Malian diplomat in Saudi Arabia, leads Ansar Dine and is no doubt chummy with the House of Saud.

Tuaregs are like the African equivalent of Kurds – a culturally distinct people without a land of their own – and their struggle for autonomy is the result of failed development policies in the north, and animosity toward the Mandé ethnic group who have dominated state institutions since independence in 1960, and clearly failed to promote an inclusive national identity. For anyone who has ever listened to the tunes produced by Tuareg musicians, which fuse Hendrix-influenced guitar lines with groovy Saharan rhythms, you’d know that not all Tuaregs are the Takfiri head-cutting type. When al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and Ansar Dine hardliners took over northern cities such as Gao and Timbuktu, they imposed a foreign brand of sharia law that locals detested, prompting a massive refugee crisis to neighboring countries. Like their pals in the Taliban who dynamited two 6th-century statues of Buddha carved into a cliff in central Afghanistan in 2001, the jihadis of Azawad took to demolishing the gorgeous ancient mud-mosques of Timbuktu, as well as burning ancient manuscripts that told of a time when the besieged city was sub-Saharan Africa’s intellectual hub. As chaos ensued and Malians felt threatened by the Islamist’s threats to expand southward toward Bamako, the frogs came marching in…

“The objective is the total re-conquest of Mali”

There is no doubt that many Malians support France’s move to militarily intervene and in doing so, they were able to push the hardliners out of the cities, but make no mistake – Paris is in this for its own economic interests. According to reports, few civilian casualties have directly resulted from French intervention and the military’s conduct has been relatively clean – the same cannot be said for their counterparts in the Malian army, who have purportedly killed and tortured dozens of civilians over suspicion of aiding the rebels. The French in all likeness turned a blind eye to these abuses since they worked closely with Malian forces. French President François Hollande was greeted with enormous praise and jubilance during his one-day visit to Bamako, so much so that he described the visit as the “the most important day in [his] political life”. Unfortunately for Papa Hollande, one could not imagine him getting such a warm reception on the streets of Paris.

In France’s current climate of staggering unemployment and austerity, Hollande saw the Islamist advance in Mali as a threat to the French economy, because two-thirds of France’s electricity comes from nuclear power, which is reliant on steady flows of uranium, mostly from Mali and neighboring Niger. Paris is also one of the leading exploiters of Malian gold, of which Bamako pockets only a meager 20 percent profit. Hollande made the final decision to intervene after a personal appeal from interim President Dioncounda Traoré, but the murky motives were no different from the colonialist days of "Françafrique" – a modern ode to the policy of a "hegemonic France". Take it from French Finance Minister Pierre Moscovici, who claimed“French companies must go on the offensive and fight the growing influence of rival China for a stake in Africa’s increasingly competitive markets”. French Defense Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian spells it out a little clearer when he was quoted saying that objective of intervention was “the total re-conquest of Mali”.

Paris justified its intervention over concerns of terrorism, but how could anyone possibly take this position seriously when France championed the arming and funding of jihadist fighters in Libya, while it continues to do so in Syria? Let’s get this straight – France supports hardline rebels who have executed civilians and destroyed historical sites in Syria, but it is against hardline rebels who have executed civilians and destroyed historical sites in Mali. This is the ‘Good Terrorist-Bad Terrorist’ dichotomy at work, which exposes the double standards of policy being taken by most west European capitals. Qatar and Saudi Arabia, both the chief financiers of the rebels in Syria, are also suspected of aiding the Islamists in Mali. Given the close relationship between Doha and Paris, it looks as if both countries are behaving in a way that serves each other’s interests. As cynical as it may seem, it looks like France has postured itself as the problem solver of a problem it had a hand in creating, with the objective of reasserting its corporate muscle over its colonial sphere of influence.

Frogs on the electoral menu

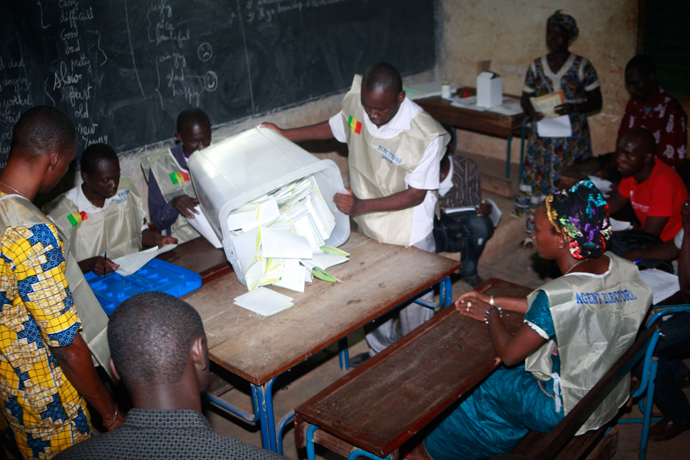

Low public participation and reports of electoral irregularities throughout Mali’s five-decade history since independence are a testament to its democracy being rather fragile, and while the situation today is less bleak, it's still not very different. Mali recently held the first round of its 2013 elections, the first since the coup, and since no candidate cleared the 50 percent needed to win outright, the second round of voting will commence on August 11. In the recent polls, official figures suggest a turnout of 51.54 percent, shattering the previous record high of 38 percent. After the country’s descent into instability, it’s clear that these elections were viewed as critical to Mali’s recovery and future development. Despite a firm argument that Mali isn’t ready for these polls due to some 173,000 Malian refugees residing in neighboring Burkina Faso, Mauritania and Niger, as well as the inaccessibility and under-representation of the north, there is a push from outside to hold these polls and install a government deemed legitimate by the international community.

The two main contenders in the elections are both from Mali’s Paris-educated political elite; former Prime Minister Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, referred to as IBK, has ties to Hollande and France’s Socialists and is expected to win the second round of voting. His competitor is former Finance Minister Soumaila Cissé, a former software engineer with IBM. During the first round of voting, Keïta came in with 39 percent to Cissé’s 19 percent – so the overall winner will likely have a weak mandate. There is some $4 billion in international reconstruction and development assistance on hold until an elected government emerges, and one would imagine that much of that would go to improving the infrastructure needed for foreign investment, and the enormous returns that will follow. One should ask themselves who the more significant benefactor of aid to Mali will be – the people, or the foreign-firms that reap exorbitant profits?

It isn’t coincidence that half the population of Mali lives on less than $1.25 per day and a third of the population is malnourished, despite the country holding tremendous natural riches. Regardless of who wins the elections, the new regime and its European backers seek to maintain the status quo. Despite French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius claiming that the war in Mali would last only weeks, he recently announced that 1,000 French soldiers would be stationed in Mali permanently, in addition to a 12,600-strong UN peacekeeping contingent. France has expressed support for increased Tuareg autonomy, and had a hand in peace accords signed between the interim government and the MNLA rebels, effectively handing over sovereignty of Kidal and the northern regions to the MNLA – a move that has enraged many ordinary people in the south. France made its motive of re-conquering Mali very clear – but is it now laying the groundwork to divide it by offering support to the fighters it intended on ousting by force? Paris may well be trying to boost its credentials as a mediator, but the Sudanese experience tells us that anything is possible if it’s good for business. Ansar Dine and AQIM fighters, many of whom are entrenched in Mali’s northern mountainous regions, have switched their strategy from holding cities to guerilla warfare. Given the enormous societal, economic, and security challenges that need to be overcome, this conflict may yet become Africa’s Afghanistan.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.