‘Too many questions’ in UN chemical weapons report to blame Damascus

While many in the West asserted that the UN report on August sarin attack in Syria all but proves the Syrian government was behind it, a closer look on it shows inconsistencies which clash with that narrative, says political expert Sharmine Narwani.

“I am certainly not saying that the UN team was trying to cover anything up. But I think some of this was staged and manipulated for impact,” she told RT.

Narwani, who is a senior associate at Oxford University, detailed her doubts about the UN report and the conclusions drawn from it in a piece she co-authored for the English-language branch of Al Akhbar, a Beirut-based newspaper.

The piece points to some facts mentioned in the report, which those accusing Damascus of the incident don’t take into account, but which also may cast doubt on that scenario. For instance The UN inspectors had to conduct their probe in tight time constraints, spending just two hours at one location and five-and-a-half hours at the other.

Both locations are controlled by rebel forces and were not cordoned off until the UN team arrived. On the contrary, the report mentions on several occasion that potential evidence they were presented was “being moved and possibly manipulated.” A similar problem arises with witnesses interviewed and victims sampled by the UN, who had been pre-screened by the rebels.

“It was a questionable exercise from the start. If you cannot have proper access, random sampling and the time you need in which to conduct a thorough investigation, what was the point?” Narwani wondered in a comment for RT.

The particular evidence the UN team reports are open for interpretation, the Al Akhbar piece said. One is inconsistency between human and environmental samples gathered at Moadamiyah, the area in West Ghouta which the inspectors visited on August 26 before moving to a second location. Alleged victims of the attack there tested highest for sarin exposure in the entire sampling, but environmental samples showed no traces of sarin.

Some of the samples in the area contained sarin degradation products, but at the same time many samples gathered from the other area, which were taken days later tested positive for sarin. A scenario, in which the victims were exposed to sarin somewhere else and brought to Moadamiyah for UN inspectors to investigate, is one possible explanation.

The authors also cite American chemical weapons expert Dan Kaszeta, who pointed out that the 36 survivors tested by the UN mission are too small a sample from statistical point of view to represent the entire population of affected victims. He also wonders why the number of victims showing symptoms of more serious sarin exposure was so large compared to those showing milder symptoms.

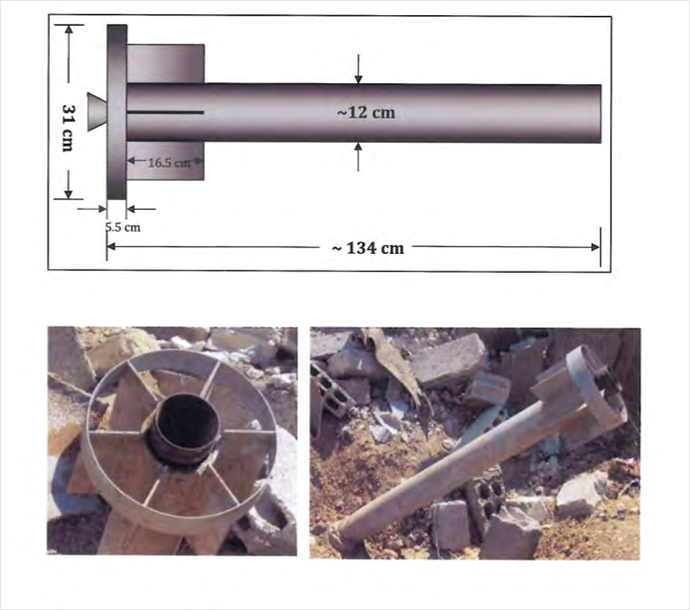

Finally there are questions to the munitions examination conducted by the UN, which many reports said proved beyond doubt that the sarin attack originated from a base of the government troops. Of the five munitions mentioned in the report as possible sources of sarin, only two provide a trajectory date.

One was successfully identified and could have been fired from the base in question, but it didn’t test positive for sarin. The other one is a ‘mystery missile’ with sarin traces, the range of which remains in question. Given its larger caliber, it could have been fired from a rebel-controlled area located further from the impact site that the government base, the authors argue.

“There are just too many questions. And unfortunately people have leaped ahead with stark answers,” Narwani told RT. “It’s not the case. Nobody is able to make a conclusive determination of any kind based on the evidence that the UN team provided.”

The UN report gave the grounds for US and some other Western nations to reiterate their demands for Syrian President Bashar Assad to be ousted and possibly tried for war crimes. Narwani agrees that the perpetrators of the chemical attacks must be brought to justice, but suggests not jumping to conclusions over an issue of such importance.

“We need to identify culpability here and we cannot do it on the basis of the current report of the United Nations. And it’s very dangerous to extrapolate from a report with these many holes,” she said.

“What’s important here is that the UN as the result of all these holes in its original report needs to then address these and ensure for itself that it has the proper access and time to investigate other areas of alleged chemical weapons attacks,” she added, referring to the return of the UN inspectors to Syria this week.

Narwani called on Russia to make public the evidence that it presented to other UN Security Council members and which, Moscow says, proves that rebels have possession of chemical weapons.

She also said that parties involved in the Syrian crisis in any way should pursue less their own goals and focus on the important part, which is stopping the bloodshed.

“We’ve been stalemated for a very long time in this conflict,” she said. “I think an end is possible, but the rhetoric needs to stop, things need to start being evidence-based and the headlines need to show a little bit more responsibility.”

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.