Glacial aftershock: Pine glacier sheds another block of ice (PHOTOS)

Antarctica’s fastest melting glacier, the large ice stream Pine Island Glacier, has shed another block of ice into Antarctic waters.

The glacier, responsible for about 25% of Antarctica's ice loss, spawned an iceberg after ”a kilometre or two” of ice broke off from the shelf’s front.

While the loss was miniscule compared to previous giant ice losses, it presents further evidence of the ice shelf’s fragility, according to NASA.

.@AntarcticPIG lost yet another chunk: https://t.co/840ilfyzs3pic.twitter.com/6caEIpJwrj

— Allen Pope (@PopePolar) February 15, 2017

The break was about ten times smaller than an event in July 2015 which saw a 30-kilometer-long (20-mile) rift develop below the ice surface before breaking through and calving an iceberg spanning 583 square kilometers (225 square miles).

“I think this event is the calving equivalent of an ‘aftershock’ following the much bigger event,” Ian Howat, a glaciologist at Ohio State University, said.

“Apparently, there are weaknesses in the ice shelf—just inland of the rift that caused the 2015 calving—that are resulting in these smaller breaks.”

In August 2013 an iceberg, six times the size of Manhattan, calved off of Pine Island Glacier.

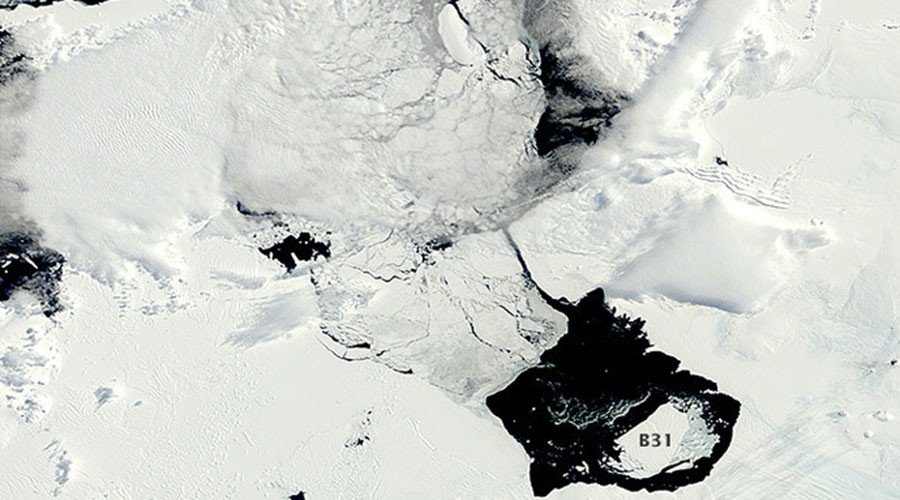

B-31 which measures 32 kilometres by 19 kilometres with a height of 500 metres is under NASA observation as it continues to drift to sea.

NASA is paying close attention to the Pine Island glacier as evidence suggests even faster loss of ice in the future. It already delivers about 79 cubic kilometers (19 cubic miles) of ice per year to Pine Island Bay.

Calving, Pine Is glacier; moves more ice into ocean than any other drainage basin worldwide #Sentinel2@ESA@ESA_EO@GreatWhiteCon@sgascoinpic.twitter.com/D9URmafY0U

— The Antarctic Report (@AntarcticReport) January 31, 2017

This latest image was captured by NASA’s Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 on January 26 after the break.

Scientists warn that more small rifts persist about 10 kilometers (6 miles) from the ice front and expect that these will result in more calving in the near future.

“Such ‘rapid fire’ calving does appear to be unusual for this glacier,” Howat said, but admitted it fitted “the larger picture of basal crevasses in the center of the ice shelf being eroded by warm ocean water, causing the ice shelf to break from the inside out.”