Dozens of ex-Stasi staff remain employed at archives of Germany’s former secret police

The Federal Commission for the Stasi Archives – the East German secret police – was born shortly after German reunification. The agency’s employment of ex-Stasi members is fuelling fear that records of its wrongs will be lost in the annals of history.

The commissioner in charge of the agency admitted in a recent

interview that 37 ex-Stasi staffers remain.

“There are still 37 of them here. Five [out of an original

48] have been moved on, five have left for age reasons, and one

of them has died,” former dissident journalist and current

commissioner Roland Jahn told Germany’s Tagesspiegel newspaper on Friday.

He admitted that the issue was harder to resolve than originally

anticipated. Under German employment law, public servants can

only be moved to “comparable” posts in other state

agencies.

“Only alternative jobs are organized in other federal

administrations,” he said. “But many employees say, ‘I

do not think about changing.’ And so the whole affair is

delayed.” The agency has some 1,600 members of staff.

The Federal Commission for the Stasi Archives (BStU) was established by the German government in 1991. Joachim Gauck – now President of Germany – became Federal Commissioner for the agency in 1990, heading up the new service. Its role was essentially to investigate Stasi crimes and manage the archiving of those offenses, as well as to protect the files so that people could access those which concerned them. “They can then clarify what influence the Stasi had on their destiny,” the BStU said

However, many have raised fears that ex-Stasi agents could easily

destroy the records while working for the agency.

The Stasi had approximately 5.1 million data cards in its

enormous archive, which also included samples of sweat -

“jars with body odor samples taken from people who had been

examined and arrested,” according to German History in

Documents and Images (GHDI).

The association also reported the widescale destruction of

documents in order to conceal crimes of the government in 1990.

“During the final days of the GDR regime, the Stasi

desperately tried to destroy the archive before it could be

seized by opponents,” WikiLeaks stated during the release of

a report in 2007.

Gauck gave permanent contracts to ex-Stasi workers around 1997.

In his 1991 book ‘The Stasi Files,’ he defended their re-hiring.

"We couldn't have done without their specialist knowledge of

certain branches and the Stasi's archiving system,” he said.

Klaus Schroeder, a historian at Berlin’s Free University told the

Guardian that “ultimately, the responsibility for giving

these people uncontrolled access to high-profile files lies with

Gauck.”

The neologism ‘Gaucken’ even crept into German discourse and came

to mean “the request and viewing of old Stasi files.” A

less flattering variation also exists: “to always speak

incessantly on the same theme in conversation.”

In the 2007 leaked report, it was first revealed that: “The

BStU [Stasi files commission] employed at least 79 former Stasi

members. At the time of the report (May 2007), 56 remained in the

employment of the agency, including 54 former full-time Stasi

members and two former ‘Unofficial Employees’ (informers).”

The report, written by Prof. Dr. Hans Hugo Klein of the Christian

Democratic Union (CDU) and Prof. Dr. Klaus Schroeder, spawned

suspicion that records of incriminating actions of some Stasi

staffers could have been modified or destroyed.

Jahn described it as “intolerable” during his inaugural

speech in 2011 that any victims of the Stasi’s methods would have

to encounter old employees.

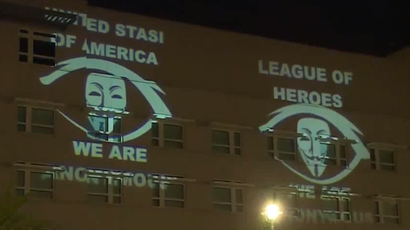

German politics has plunged into a whirlpool of anti-Stasi

rhetoric in recent months, with reports emerging over the past

two weeks that German Chancellor Angela Merkel compared the

NSA’s spying to that of secret police in East Germany.

“I find it absurd to equate the NSA and the Stasi – it clouds

the view. It doesn't help us in clearing up the current

intelligence scandals, and it trivializes the work of the Stasi.

They didn't only gather information but also locked up anyone who

commented critically on the state. But the NSA debate has shown

how important it is to speak out when fundamental human rights

are being violated,” Jahn added.