Questions on Ukraine the West chooses not to answer

Ukrainian and Western refusal to answer Moscow’s hard questions explains Russia’s tough stance on the crisis in Kiev.

Ignoring Russian concerns is a Western habit adopted after the Soviet Union’s collapse; when NATO bombed Yugoslavia; during the recognition of Kosovo as an independent state, and the US push to install an anti-missile shield over Europe that can target Russia.

It also happened recently when Western diplomats flocked to Ukraine to smile and wave and lobby their interests in a future Ukrainian government, while accusing Russia of meddling in Ukrainian affairs.

But it seems that in Ukraine lies Russia’s red line and Moscow no longer takes “don’t know, don’t care” for an answer.

Here’s the questions.

1. Why did the opposition oust Yanukovich after he conceded to their demands?

On February 21, Yanukovich and the three Ukrainian parliamentary faction leaders signed a reconciliation deal co-signed by Foreign Ministers of France, Germany and Poland. A gesture that their countries would serve as agreement guarantors.

The agreement provides a de-escalation roadmap of constitutional reform, a national unity government, early presidential election and disbandment of Maidan fighter groups.

Hours after it was signed, Right Sector radicals, key to the violence unleashed in Kiev which left a hundred people dead, gave Yanukovich an ultimatum: resign or face a siege of his residence.

Against Moscow’s advice, Yanukovich fled.

Vladimir Putin’s comments illuminate the Russian position here: "He [Yanukovich] had in fact given up his power already, and as I believe, as I told him, he had no chance of being re-elected.. What was the purpose of all those illegal, unconstitutional actions, why did they have to create this chaos in the country? Armed and masked militants are still roaming the streets of Kiev. This is a question to which there is no answer."

Russia says the February 21 agreement must be implemented. The opposition signed it yet allows an uncontrolled militia of violent armed radicals send fear and loathing across a large swath of Ukraine.

The US says the agreement no longer matters – because Yanukovich fled. The EU signatories don’t seem to be bothered about it either.

2. Why is the coup-appointed govt replacing oligarchs linked to Yanukovich with... oligarchs?

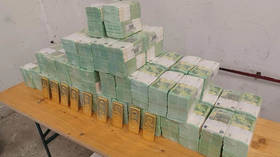

Popular resentment of Yanukovich blossomed over corruption. Protesters pointed to power abuse, theft and allowing linked-oligarchs raid businesses of other clans. Evidence came readily after they fled - photos of their homes’ sumptuous interiors.

But the new self-appointed govt is replacing Yanukovich’s oligarchs with their own. Kiev just appointed billionaires as governors of Donetsk and Dnepropetrovsk respectively, a move that also drew Putin’s ire: "Mr. Kolomoisky was appointed governor of Dnepropetrovsk. This is a unique crook. He even managed to cheat our oligarch Roman Abramovich two or three years ago. Scammed him.."

Both hold major assets in their respective regions and thousands depend on them for work. Both appointments are meant to stabilize a volatile society and ensure loyalty to the capital but critics say Kiev is reinventing fiefdoms to nobility in exchange for servitude. For Putin, who famously excluded oligarchs from politics, the move is an anathema.

3. Why did the post-coup parliament strip Russian language of its regional status?

A bill repealing a law on regional languages was among dozens

rubber-stamped by a chaotic Ukrainian parliament in the first

post-coup days. It allowed the Ukrainian nationalist and

anti-Russian Svoboda (Freedom) Party put a feather in its cap.

Yet it sent a ripple of hostility south and east from Kiev, where

Russian-speakers are a large minority or even majority.

Kiev pledged to restore the status of Russian but now says the

acting Ukrainian president won’t sign such a bill into law.

4. Why did Kiev attack the Constitutional Court?

Several Constitutional Court judges were accused of violating their oath and abruptly fired amid coup govt orders they be prosecuted. The judges branded this as an attack on the principle of separation of powers. Putin called it "monkey business".

As Yanukovich was not procedurally impeached but through a simple show of hands the legality of his impeachment is open to challenges taken by several Ukrainian regions and, diplomatically, by Russia. The Ukrainian Constitutional Court is the proper authority to rule on the issue yet the new Kiev admin is mooting totally disbanding it and giving its functions to the Supreme Court.

5. Why would the West support the coup in Ukraine?

From the Russian perspective, the West fueled the fires of protest and ensured the Ukrainian government was toppled. Now it is attempting to legitimize its factious replacement. What Russia calls an unconstitutional coup, the West is branding a public revolution. It is possible that it is both.

Moscow does not challenge the reality. It doesn’t seek a Yanukovich return to power. It would work with the people who ousted him, as it did with the Yushchenko presidency. But Moscow demands the Kiev coup govt carries a national mandate to govern, in both east and west . Without it, any government is unsustainable.

Putin’s position is that it now maybe too late, despite his repeated warnings Ukraine would polarize. "Did our partners in the West and those who call themselves the government in Kiev now not foresee that events would take this turn? I said to them over and over: Why are you whipping the country into a frenzy like this?"

A stable Ukraine is essential for Russia for many reasons, humanitarian being just few of them. Of course Russia wants ethnic Russians in Ukraine to be safe from potential violence and persecution. But there are also more pragmatic considerations as well.

There’s the Black Sea Fleet, strong economic interdependence and there is gas. Ukraine transits Russian natural gas to Europe and is thus essential to the Russian and European economies. Yet now a desperate Kiev mulls privatizing its gas pipelines to fill its empty coffers, while Moscow’s questions remain unheard.