NSA scandal: Germans hold out for ‘change they can believe in’

It is difficult to imagine how a significant rift in trans-Atlantic relations could emerge without the involvement of Germany, the European Union’s most populous, financially solvent and politically powerful member.

It continues to host tens of thousands of American troops on its soil, and with its impeccable capitalist credentials, track-record of dutiful political decision-making, enviable manufacturing base and ability to criticize English-speaking nations in their own language, Germany is always able to make a good case for its views on the international stage.

Since Germany is not a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council nor closely bound to significant former overseas possessions, it is more likely to disagree with American expansionist policies than Britain or France. Permanently half a step out of sync with the P-3 (the USA, UK and France) in this regard, Germany – a loyal NATO-member during the Cold War – has become the ultimate swing state of international relations over the past decade.

With fears of Soviet invasion and fond memories of Allied troops handing out candy in the aftermath of WWII fading rapidly into the past, the Second Iraq War presented a major turning point in US-German relations and a sharp disillusionment of many Germans with American foreign policy.

Eventually proven right in its skepticism of Anglo-American claims that Iraq was stockpiling weapons of mass destruction, Germany has remained decidedly unenthusiastic about Western-led interventions ever since. Most notably, in 2011 Germany – along with China and Russia – refused to endorse UN Security Council Resolution 1973 which enabled limited military engagement during the civil war in Libya.

Several US officials, including former US Ambassador to NATO Nicholas Burns, publicly criticized Germany’s decision to abstain from voting on the Resolution. This criticism provoked an intense debate within Germany and soured relations just a little bit more. The NSA mass surveillance programs revealed by Edward Snowden last year put another nail in the coffin of the once so-rosy US-German relationship.

Voices against NSA spying

While it seemed at first that NSA surveillance in Germany might be dealt with in a purely diplomatic context with all parties agreeing to make a few cosmetic changes before sweeping the issue under the rug, German politicians have become increasingly vocal about just what the American administration will need to do to mend fences with them.

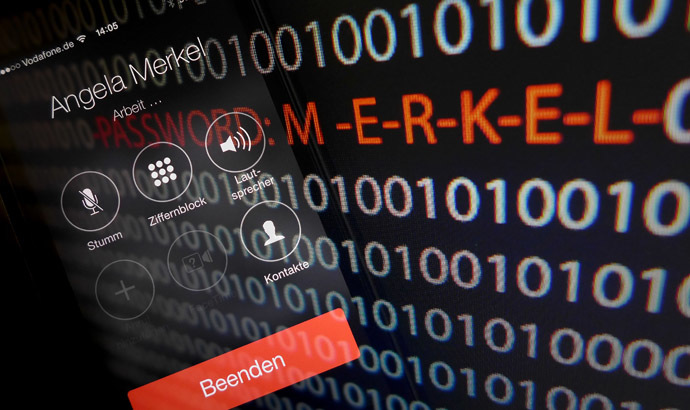

This stance – which has been taken up by members of both parties in Germany’s governing ‘grand coalition’ (the center-left SPD and Chancellor Merkel’s center-right CDU/CSU) – has proven far more popular than Merkel’s original mild reaction on learning that the NSA had hacked her private cell phone. World leaders may be inclined to take some measure of spying on themselves with a grain of salt, but German voters were inflamed, particularly because President Obama had previously denied that the NSA was conducting operations against German targets. With an electorate feeling shocked, angered and betrayed, politicians across the political spectrum soon realized that this was not an issue to be ignored.

The SPD’s leader in parliament, Thomas Oppermann, has taken a strong stance against the NSA programs, contemplating asylum for Edward Snowden, demanding a No-Spy-Agreement between Germany and United States and threatening legal action. The SPD currently holds the Ministry for Justice and has, according to a DPA report, stated that it will not exercise its ability to prevent criminal prosecutions related to NSA spying on government figures. In particular, German politicians have been less than receptive to the olive branch extended to them (and the rest of the world) via Obama’s reform plans for the NSA.

Justice Minister Heiko Maas has characterized the proposed NSA reforms as merely a “first step,” stating that only a No-Spy Agreement would suffice to allay his concerns. Elmar Brok, a CDU Member of the European Parliament and Chairperson for the Committee on Foreign Affairs, harshly criticized Obama’s speech on NSA reform as window-dressing, lending his views weight by explicitly stating that the pending Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership between the European Union and the US should not be signed before the issue of data protection was completely resolved.

He was echoed in this sentiment by fellow CDU/CSU politician Stephan Mayer who demanded “concrete action,” while government spokesperson Steffan Seibert, while delivering the government reaction to Obama’s speech, reminded his audience that the government expected its allies to respect German law on German territory. Most strongly of all, Merkel herself is alleged to have compared NSA surveillance activities to the actions of the East German Stasi in a recent confrontation with Obama.

No to shooting the plane down

While this strong stance on the issue of mass surveillance may cause their Anglo-Saxon counterparts some anxiety, Germany’s ire shouldn’t surprise them. While Western values of individual freedom and democracy were imposed on Germany more or less by fiat following the Second World War, in the intervening years these values have deeply penetrated the German legal system and public opinion. Both the German constitution, with its robust protections of individual rights (including privacy), and the principles of international law (especially the prohibition on the use of force) are revered points of cultural reference and perceived as non-negotiable. In other words, Germans took all of the human rights talk seriously, apparently not having received the memo on how to use it merely for political spin.

To give an example: while British and American politicians have repeatedly vowed to shoot down any hijacked passenger plane which might be used in a 9/11-style attack, such a situation proved a legal and moral conundrum in Germany. With a 70-year legal tradition that enshrines deep respect for the sanctity of life and human dignity, the topic provoked months of heated debate. This debate culminated in the Bundestag passing a law that permitted authorities to shoot down a hijacked passenger plane in certain circumstances, a law that was immediately quashed by the Federal Constitutional Court on the grounds that it contravened citizens’ basic rights.

Similarly, Germans feel deeply about the issue of surveillance, as for many of them the experience and consequences of repressive state surveillance are well within living memory and deeply unacceptable on a cultural level. Many Germans are thus willing to lend a helping hand to anyone who opposes such practices. Thus, just as Germany became a focal point for resistance to the Second Iraq War, it is beginning to become something of a magnet for transparency activists, with Jacob Appelbaum and Sarah Harrison currently residing in Berlin where they face fewer obstacles in conducting their work.

An American citizen, Appelbaum – an early WikiLeaks volunteer and TOR project member – has relocated to Germany to avoid harassment from US authorities, while Harrison – the WikiLeaks worker who escorted Edward Snowden to Moscow – has cited fears of legal prosecution in her native Britain as the reason for her choice to remain in Berlin.

While Germany and the rest of what Donald Rumsfeld once referred to as “Old Europe” are still firmly rooted in the Western-centrist tradition and do not espouse any particularly radical policies, they would like to move from head cheerleader to equal partner within the Western bloc of developed nations and have their core values respected.

Individual privacy is, for good reason, one of their core values and with the support of their electorate, German politicians are willing to hold out for change their constituents will believe in.

Having lost a great deal of international credibility over the past decade, the US now finds itself in a delicate position. While the American administration would obviously like to get its surveillance programs off the international agenda as quickly and as quietly as possible, the Germans have made clear that it will stay on their agenda, and that they will use their clout to keep it on the European agenda, until they receive a concession that makes it worthwhile for them to change their minds.

If the US wants to fully repair its relationship with Germany it will have to take some meaningful action on this point or risk further alienating a nation that has previously proven to be one of its most loyal allies.

Roslyn Fuller, for RT

Dr. Roslyn Fuller is the author of Ireland’s leading textbook on international law. She was educated at the University of Goettingen in Germany.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.