Four indicted in Feb. recall of 8.7 million pounds of contaminated beef

Four people from the slaughterhouse at the center of a massive beef recall in February have been indicted for purposely allowing diseased cattle into its processed meat and misleading health inspectors.

Federal prosecutors on Monday this week claimed the owners of Rancho Feeding Corp., a Northern California beef processing plant, schemed with employees to butcher about 79 cows with skin cancer of the eye rather than stopping plant operations during inspector lunch breaks. The government also said that plant workers swapped the heads of diseased cattle with heads of healthy cows to hide them from inspectors.

The company’s co-owners, Jesse Amaral, Jr. and Robert Singleton, were indicted, along with yardman Eugene Corda and foreman Felix Cabrera. Amaral and the two employees were charged with 11 felony counts, including distribution of adulterated and misbranded meat, mail fraud and conspiracy. Singleton was charged with only one count of distributing adulterated, misbranded and uninspected meat.

Amaral pleaded not guilty during a Monday morning hearing and was released on $50,000 bail; the status of Cabrera and Corda is still pending. Singleton is expected to plead guilty and cooperate with the US Attorney’s Office in the prosecution of the other three defendants, KQED reported.

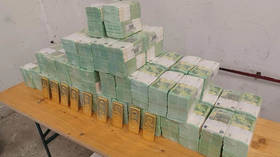

In February, Rancho recalled over 8.7 million pounds of beef products because it used "diseased and unsound animals," the US Department of Agriculture said in a statement. The beef, which also lacked proper federal inspections, was produced between January 1 and January 7 and was unfit for human consumption. The meat was shipped to California, Florida, Illinois and Texas, the department’s Food Safety and Inspection Service said at the time. Despite the massive size of the recall, the indictment only focused on 180 head of cattle.

It’s rare for a recall to lead to a federal indictment, Bill Marler, a food safety attorney, told KQED.

“There are very few criminal prosecutions generally in food cases, and there are very few and far between in meat cases,” Marler said. “They’re facing some severe jail time and some severe fines.”

Between mid to late 2012 and 2014, Rancho processed and distributed meat that had not passed USDA inspections, including about 101 condemned cattle and 79 cancerous cattle from January 2013 and January 2014. Rancho paid Cabrera $50 for each condemned carcass that was distributed, the indictment said.

According to the charging documents, Singleton purchased some cattle that showed signs of epithelioma ‒ lumps or other abnormalities around the eye ‒ that made them less expensive than animals that appeared healthy. Amaral then directed employees to process cattle that had failed an inspection by a USDA veterinarian and stamped with “USDA Condemned.” Cabrera then directed employees to carve the stamp out of the cattle carcasses and to treat the meat the same as if it had passed inspection, the indictment alleged.

The two owners also directed Corda and Cabrera get around inspection procedures for cattle with eye cancer by swapping the diseased cows for cattle that had already passed inspection and were awaiting slaughter, the indictment said. Cabrera or other employees ‒ at his instruction ‒ “placed heads from apparently healthy cows, which had previously been reserved, next to the cancer eye cow carcasses. This switch and slaughter of uninspected cancer eye cows occurred during the inspectors’ lunch breaks, a time during which plant operations were supposed to cease,” prosecutors claimed.

The swapped meat was then distributed, and Amaral mailed out 17 fraudulent invoices for the cattle to the farmers the animals were purchased from. “Specifically, [Amaral] falsely advised farmers that their cattle had died or been condemned, knowing that the cattle had in fact been sold for human consumption,” according to the court documents. He and other employees at his instruction then created invoices to charge the farmers handling fees for disposal of the carcasses, instead of compensating them based on the sale price.

The four men face up to three years in jail and $250,000 for each felony charge, according to KQED. There could also be lawsuits stemming from the recall, though Marler doesn’t believe there will be any money left over after the fines to pay the affected farmers. One California rancher, Bill Niman, said he lost $400,000 when he had to dispose of 30 tons of grass-fed meat he was blocked from selling after the contaminated meat came to light in February.

There have been no reports of illnesses linked to the products, the Associated Press reported. More than 1,600 food distributors in the United States and Canada were alerted to the recall that asked consumers to return products, including beef jerky, taquitos, hamburger patties and Hot Pockets frozen sandwiches.

Rancho stopped operations after the recalls. In March, the USDA allowed another Northern California company, Marin Sun Farms, to take over the shuttered slaughterhouse.