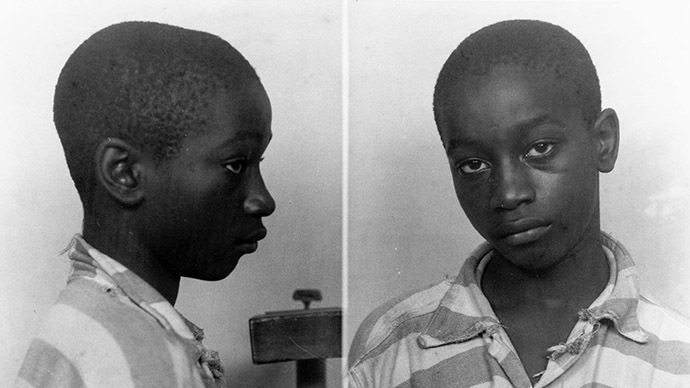

14-year-old exonerated for double murder 70 years after his execution

It took 70 years, but a 14-year-old African American boy from Alcolu, South Carolina who was executed for allegedly killing two white girls has now been exonerated of murder.

In a ruling issued Wednesday by Circuit Judge Carmen Mullen, the murder conviction against George Stinney was vacated over concerns that the young boy’s constitutional right to a fair trial was violated to the point that his name should be cleared, WIS TV reported.

Stinney, who was so small at the time of his execution by electric chair that he had to sit on a phone book, is often cited as the youngest American to be put to death by the state in the 20th century.

During his trial in 1944, Stinney’s white lawyer did not present witnesses or cross-examine witnesses presented by the prosecution. In 2009, Stinney’s sister claimed in an affidavit that her brother could not have killed the two young girls because he was with her at the time their deaths occurred.

"The state, as an entity, has very unclean hands," attorney Miller Shealy argued at a hearing in January, as quoted by the Huffington Post.

According to the prosecution, Stinney admitted to murdering the two girls – Betty June Binnicker, 11, and eight-year-old Mary Emma Thames – by beating them with a railroad spike. The boy’s family and other advocates argue this confession was coerced, and little evidence from the trial – including the spike – remains.

The trial was concluded after about three hours, and a jury of 12 white men delivered a verdict against Stinney in 10 minutes.

"By not putting the state's case to the test at all, by not cross examining witnesses, not putting up a defense at all, not giving a closing argument, George was never afforded effective council and as a result his Sixth Amendment rights were violated," said defense attorney Steven McKenzie to WIS.

One relative of Binnicker testified that while the laws were different at the time of Stinney’s trial, he was “found guilty by the laws of 1944” and said the decision should stand.

Solicitor Chip Finney also defended the work authorities did in the past.

"They weren't trying to railroad every black person associated with Alcolu and these little girls” he said during the hearing. “They made a determination based on facts we don't have today that George Stinney should be detained.”

Judge Mullen disagreed, however, ruling that Stinney’s right to due process was violated.

"Given the particularized circumstances of Stinney's case,” Mullen wrote, “I find by a preponderance of the evidence standard, that a violation of the Defendant's procedural due process rights tainted his prosecution.”