California’s ‘Big One’ could trigger super cycle of destructive quakes – study

Published 23 Apr, 2015 23:43 | Updated 23 Apr, 2015 23:43

A major earthquake – the Big One – is statistically almost certain in California in the coming decades, and there is even worse news below the ground: it is likely to be followed by a series of similar-sized temblors, according to a leading seismologist.

READ MORE: Man-made earthquakes increasing in US, wastewater to blame – USGS

The current relatively quiet seismic period – in which “far

less” energy is being released in earthquakes than it is

being stored from tectonic plate motions “cannot last

forever,” said University of Southern California earth

sciences professor James Dolan while delivering a new paper

during the Seismological Society of America conference in

Pasadena.

“At some point, we will need to start releasing all of this

pent-up energy stored in the rocks in a series of large

earthquakes,” Dolan stressed.

The earthquake could spark a “super cycle,” meaning

“a flurry of other Big Ones, as stresses related to the

original San Andreas fault earthquake are redistributed on other

faults throughout Southern California,” he said.

Earthquake fault heightens California tsunami threat, experts say http://t.co/gzGsgOTXAupic.twitter.com/IkC3hiyLrd

— Paul Duginski (@CartoonKahuna) April 21, 2015

While there would not be a literal cannonade of destruction, the

earthquakes could come just decades apart, like, for example, the

7.5 major quake in 1812 on the San Andreas fault, followed by a

7.7 in 1857.

Incidentally, that was the last major earthquake in that system,

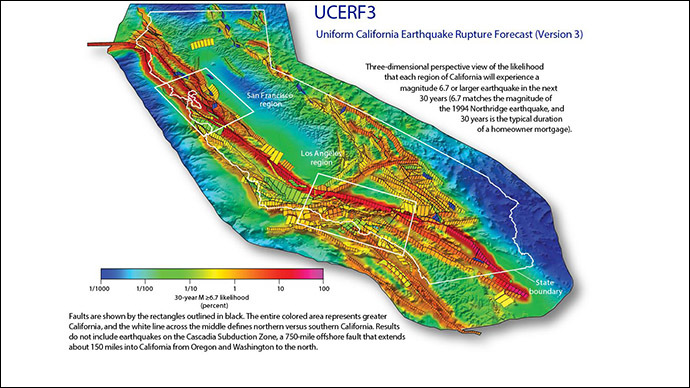

one of the factors that led the US Geological Survey to conclude

last month that there is a 7 percent chance of an earthquake

measuring 8.0 or greater on the Richter scale to occur in

California in the next 30 years alone.

Scientists behind the March report said that the fault lines in

California – which is home to almost 40 million people – are much

more interconnected than previously thought, and similarly

claimed that “tectonic forces are continually tightening the

springs of the San Andreas fault system, making big quakes

inevitable.”

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake struck the coast of Northern California at 5:12 a.m. on Wednesday, April 18. pic.twitter.com/6b0IQnNGDj

— Historical Pictures (@HistoryTime_) April 18, 2015

Dolan made his discovery while studying the Garlock fault line ‒

state’s second-biggest. He said the Garlock was “switched

off” for 3,500 years before creating four major earthquakes

from 250 AD to 1550. During that period, the fault lines were

moving four times as fast, as during the pause.

“We’re not focused especially on the seismic threat posed by

the Garlock,” said Dolan.

“This study focuses on the deeper scientific significance,

the more general importance of how faults interact with one

another over long time and distance scales, and fundamentally on

helping us to understand how faults store and release

energy,” he added. “These are issues of absolutely basic

importance for our understanding of seismic threats from all

faults.”

The most destructive recent earthquake in California was the

Northridge in 1994, which caused more than 50 deaths and $20

billion worth of damage despite its modest magnitude of 6.7.