After Dakota Access victory, protesters take aim at Louisiana pipeline

Environmentalist groups are mobilizing against the Bayou Bridge pipeline in the swamps of southern Louisiana, seeking to repeat the success at Standing Rock, North Dakota. They are taking on the same company that is behind the Dakota Access Pipeline.

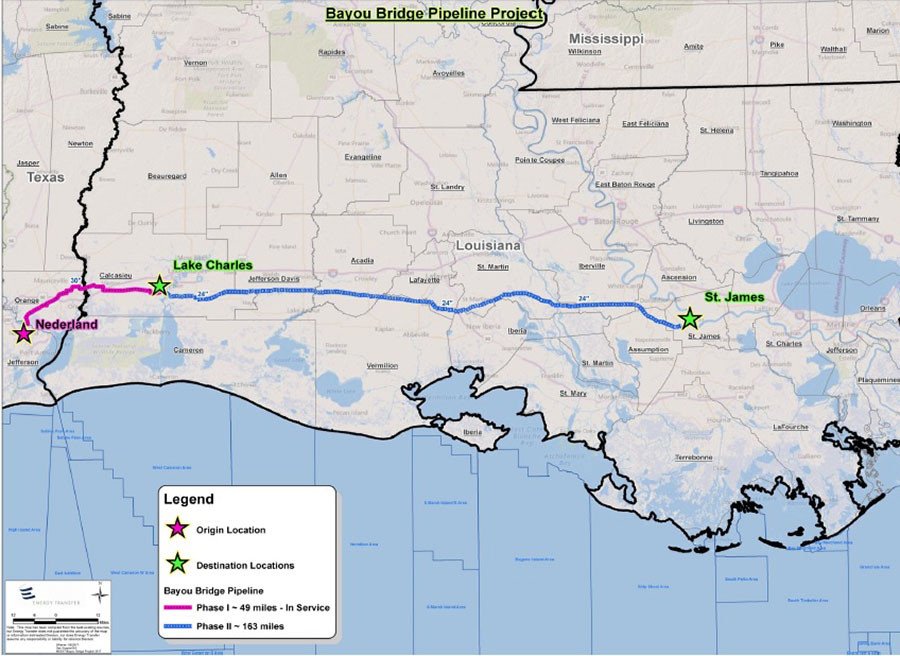

The extension, proposed in 2015, would link up the existing portion of the Dakota Access pipeline (DAPL) to refineries on the Gulf coast of Texas. If approved, it would run for 163 miles between Lake Charles and St. James in Louisiana – across the Atchafalaya Basin, the largest natural swamp in the US.

Energy Transfer Partners, the company behind DAPL, seeks to begin construction on Bayou Bridge as early as March 2017, but just like in the case of Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, it requires a permit from the US Army Corps of Engineers first.

“We are a long way away from deciding whether or not to grant this permit,” ACE spokesperson Ricky Boyett told the Shreveport Times.

Meet the water protectors defending the bayou from the Dakota Access pipeline route https://t.co/TkoNJFhb1ppic.twitter.com/IMCspHnLEc

— ThinkProgress (@thinkprogress) January 14, 2017

According to the permit application, the pipeline would temporarily affect 171 acres of wetlands in the Atchafalaya watershed and result in the permanent loss of 77 acres. If approved, the Bayou Bridge extension would cross 11 parishes, traversing 600 acres of wetlands and 700 bodies of water, including wells that supply drinking water to about 300,000 families.

Hundreds of local residents packed the Galvez office building in Baton Rouge, Louisiana last Thursday, for a public hearing on the pipeline extension. Proponents of the pipeline argued that it was the safest method of transporting oil – some 280,000 barrels of crude per day – and that many pipelines already run through the basin.

The pipeline would also bring 2,500 temporary jobs – but only 12 permanent ones – according to Cory Farber, the Bayou Bridge project manager.

Protests Increase Over ETP's Bayou Bridge Pipeline in Louisiana https://t.co/y83FwSaW9t via @efjournal

— Backbone Campaign (@backboneprog) January 15, 2017

“The people who are against pipelines in general would have you believe that these are environmental disasters waiting to happen,” Tommy Foltz, executive director for the Consumer Energy Alliance, told the Shreveport Times. “A lot of these pipelines will last 100 years or more without incidences. I have a hard time seeing the negative impacts.”

Not so, according to the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, a New Orleans-based environmentalist organization. They counted a total of 144 spills, leaks or other pipeline accidents in 2016 just in Louisiana, an average of 2.7 a week.

Not In My Bayou Part 2: SBC locals head to south Louisiana to hear about proposed pipeline: https://t.co/5ErSqBfH4h

— Lex Talamo (@LexTalamo) January 16, 2017

Critics of the pipeline further pointed out that construction often leaves behind silt and “spoil banks” of displaced dirt, which increase the risk of floods and adversely impact the fish and crawfish in the wetlands. ETP’s plans include an initiative to improve water quality in the basin and clear up the spoil banks.

“Bayou Bridge is committed to restoring 100 percent of any affected area – at the company’s own expense – if there are any impacts from construction or during long-term operations,” says a statement ETP sent to RT.

In addition, approximately 88 percent of the pipeline, “including the entire crossing of the Atchafalaya Basin, will parallel existing infrastructure such as other pipelines, power lines and roads,” the company said.

“I have no problem with the pipeline if they do it right. I do like my oil and gas,” said Jody Meche, president of the state Crawfish Producers’ Association, who spoke against the pipeline at the hearing.

Meche told the Guardian he’s skeptical the ETP would actually follow through with the clean-up.

“You know how much money you’re talking about, bringing tractors back in the basin to fix all that? They’re only going to pay what they are obligated to do, and nothing else,” he said.