Bioengineers promise to 3D-print human hearts in a decade

Scientists in Kentucky predict that they’ll be able to use 3D printer technology to create a bioficial human heart in only ten years’ time.

Dr. Stuart Williams is the director of the Cardiovascular Innovation Institute in downtown Louisville, Kentucky, and he thinks his office is only a decade away from what could be one of the biggest medical marvels ever.

Heart disease is the number one killer in the United States and claims around 1 million lives annually, according to recent studies. Dr. Williams has witnessed both of his parents pass away due to the disease, and by 2020 it is expected to be the biggest life-taker on Earth. By then, however, Williams expects to be near the breakthrough point with regards to his most ambitious endeavor yet.

"America put a man on the Moon in less than a decade. I said a full decade to provide some wiggle room," Williams recently told Wired of his projected progress.

Just as 3D printers have let anyone from hobbyists to industrial designers manufacture objects as of late, Williams says he wants to use that same technology to replicate the most critical of body parts. Designers have already managed to show that 3D printers are capable of churning out fully-functioning firearms, and scientists have already explored with making organs, including a liver and an ear, with that technology. Williams, however, wants to be able to bring to life something with a beat.

“We think we can do it in 10 years — that we can build, from a patient’s own cells, a total ‘bioficial’ heart,” he said to the Courier Journal newspaper.

Speaking to local network WDRB, Williams said, "The term total bioficial heart really started here in Louisville.” In 2007 Williams joined the rank of the Cardiovascular Innovation Institute, a joint collaboration between the city’s Jewish Hospital and the University of Louisville, and once there he patented the first method in the world for using fat-derived stem cells for therapeutic use. He’s again exploring what exactly cells are capable of, and could be onto something huge.

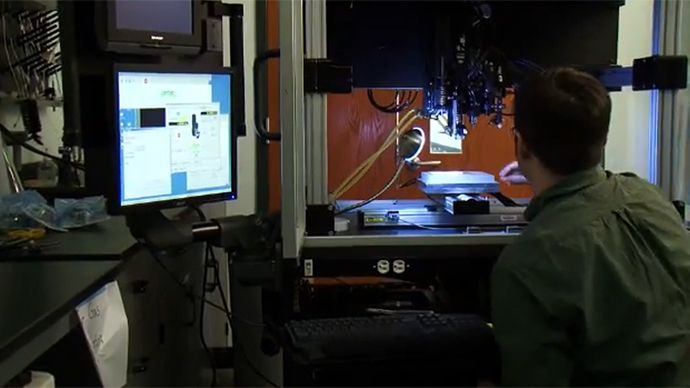

"You take tissue from a patient isolate the cells, because we're all made up of just billions and billions of cells put those cells into a machine, hit a button and it will print out a heart," he told the station. “Fifty CCs of fat is two golf ball size pieces of fat and there are enough cells in that fat to rebuild basically all of the major blood vessels in the heart.”

"If you think about building an airplane what you do is build individual parts and then assemble… We're doing the exact same thing with the bioficial heart," he added to WDRB.

That isn’t to say anyone wanting to do a little Frankensteining of their own can simply fire up their printer and then put together the pieces, of course, but Williams revealed to Wired that the process he’s been playing with isn’t near as expensive as more traditional medical procedures in the realm of heart surgery. He told the Courtier-Journal that making a bioficial heart today could cost upwards of $100,000, plus another 150k in hospital and surgery costs. Even still, though, the paper reported that the $250,000 price-tag would be less than the typical heart transplant, and doesn’t come up with the ongoing costs of anti-rejection drugs that would be required in those cases.

WDRB reported that clinical trials are already being performed on bioficial blood vessels, and Williams believes the 2023 deadline is still within reach.

"There is great interest and support [because] everyone understands this technology will lead to ancillary discoveries and new therapies to treat just part of the heart or part of the circulatory system,” he told Wired.