'Broken-souled idealist': Hacker confidante who exposed Manning testifies

Published 5 Jun, 2013 03:10 | Updated 5 Jun, 2013 14:01

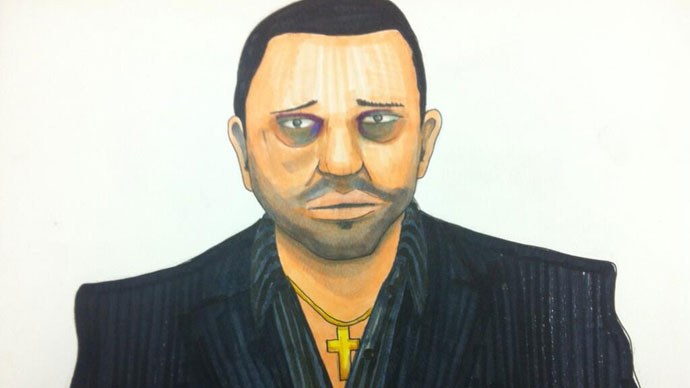

The Colombian-American computer hacker who turned Army Private Bradley Manning in to authorities surprised courtroom spectators Tuesday when he took the stand during day two of the soldier’s trial.

Read RT’s live updates on the court-martial of

Pfc. Bradley Manning.

Prosecutors called Adrian Lamo to testify Tuesday morning, an unexpected maneuver that brought gasps from within the courtroom and the nearby media center where only a handful of journalist gathered to report on the second day of the long-awaited court-martial of Private first class Manning. Not a single one of the 70 seats within the Ft. Meade press center was vacant when the trial kicked off on Monday, but barely two-dozen journalists assembled a day later when a key witness in the case was called to answer questions about the Army intelligence analyst.

Less than a week before he was arrested by American authorities in May 2010 and charged with the biggest leak of intelligence in US history, Pfc. Bradley Manning admitted to Lamo in online chats that he shared a trove of sensitive files with the whistleblower website WikiLeaks. Lamo told law enforcement officials about his conversations with Manning shortly after the two began talking on May 21, in turn prompting the private’s arrest and ultimately the trial that finally got underway in Fort Meade, Maryland this week after more than three years of waiting.

The prosecution called Lamo as their third witness on Tuesday and began their questioning by asking him to discuss his history as a computer hacker, a tenure he said started in the 90s and involved a number of high profile intrusions into the networks of the New York Times, Microsoft and others. Now 32, Lamo was practically a teenager when he became a fugitive of the law more than a decade ago before pleading guilty to computer crimes and ultimately being sentenced to serve a brief stint of house arrest and probation. Manning later learned of Lamo’s run from the FBI and reached out to him from Iraq during an apparent time of need. Now the soldier stands to spend life in prison if convicted of aiding the enemy — the most serious of the 20-plus counts the US government charged him with after Lamo turned him in.

When prosecutors began to test their witness, they asked Lamo to go back to 2010 and recall the computers and software he used during the random few chats between himself and Manning. The Army would later enlist forensics experts to scour Lamo’s laptops for more information about his online encounters with the WikiLeaks source, but the witness’s own mastery of computers had him running circles around the prosecution as he spoke from the stand.

At one point, Lamo — who admittedly suffers from Asperger’s syndrome and severe depression — eluded attorneys by offering all-too detailed descriptions of his computer habits, leaving even Army prosecutors scratching their heads.

“Mr. Lamo, you seem to know more than the common person about computers,” an Army attorney acknowledged early on during Tuesday’s questioning. Lamo agreed that he has extensive experience in the field, including proven knowledge with regards to finding ways to bypass and improve the security of certain systems. That know-how eventually led to Lamo’s criminal conviction, and later defense attorney David Coombs related it to his client’s own thirst for knowledge.

Pfc. Manning reached out to Lamo initially via emails before the chats over AOL ever began, and the prosecution asked the hacker to explain how he knew the correspondence came from the intel analyst and not anyone else.

“Based on retrieving return address information common to all email,” Lamo replied dryly.

When prosecutors pushed him to explain what that information entailed exactly, Lamo said without missing a beat, “Information indicating where it originated from which allows the recipient to reply.”

“Is that an email address?” the prosecutors asked sincerely.

“Yes, it is,” he replied, prompting snickers from the press gallery.

Lamo went on to speak about the two personal computers he used to speak with Manning, but wasn’t allowed the opportunity to discuss the now infamous chat logs until the defense began cross-examination later that morning.

Manning was the one who initiated those conversations with Lamo and didn’t wait long at all before revealing his association with WikiLeaks and his role in sending them files. Earlier this year, the soldier said in a pretrial hearing that he sent WikiLeaks US State Department cables, field reports from the Iraq and Afghan wars and a tome of other sensitive information.

“I’m an Army intelligence analyst, deployed to eastern Baghdad, pending discharge for ‘adjustment disorder’ in lieu of ‘gender identity disorder,” Manning wrote in confidence to Lamo only moments into their first IM chat.

The logs of the Manning/Lamo talks were released to the media by the hacker himself only days after the soldier was apprehended outside of Baghdad, but until now the self-taught computer security expert spoke little publically about the few days the two talked before he turned him in.

After the prosecution retired, Coombs began his turn at questioning by having Lamo admit to cracking computer network at a younger age, a decision on his part that prompted him to run from the FBI and end up on wanted posters across California.

“I committed a string of offenses, yes,” Lamo said.

Coombs raged on, subtlety intensifying his questions at a pace that lent to the counsel relentlessly wanting Lamo to enlighten the court as to his opinions of Manning and his role with WikiLeaks given what he encountered during the few Internet chats between the two.

“You were concerned about the type of information?” Coombs asked.

“Yes,” Lamo replied of the leaked Army data.

“You were also concerned for Pfc. Manning’s life?”

Again, a "Yes."

The government predicted during opening statements one day earlier this week that that they will prove that Manning went to WikiLeaks knowing he would bring harm to America. In particular, they said the soldier was aware that sharing sensitive files on the Web would mean enemies of the US — specifically al-Qaeda — could come across the information and use it to better their own battlefield strategies. Manning has insisted otherwise, though, and Coombs coaxed his one-time supposed-confidant into admitting that he was left with that same impression of the soldier during those few days of chats in the spring of 2010.

On the defense’s part, Coombs used his opening remarks on Monday to depict Manning as a young, naïve and well-intentioned do-gooder who gave Wikileaks hundreds of thousands of files with the desire of bringing about change across the globe. But during his cross-examination of the prosecution’s witness on Tuesday, Coombs all but made the man who turned his client in agree to exactly the same.

“You believed he was ideologically motivated?” Coombs asked him.

“That was my speculation.”

“You also saw him as idealistic?”

“Yes, I did.”

“He told you during your conversations that he wanted to disclose this information for public good,” Coombs recalled from the logs.

“That was his representation, yes,” Lamo said.

Coombs went on draw comparisons between the two, many of which Lamo admitted were indeed rather accurate. Both men were geeky, rather introverted computer wizzes, and both had roles in their respective LGBT communities.

“He told you that he was always the type of person that tried to investigate to find out the truth?” Coombs asked.

Lamo, in response, said that that was “Something that I could appreciate."

The prosecution objected to the questioning made by Coombs no fewer than four times during what was less than an hour of testimony, but the courtroom grew tense as the dialogue revealed not just more in common between the two, but also Manning’s fragile yet focused state during the online chats.

“He told you he was an intelligence analyst,” Coombs said, and a person who “reached out to somebody like you who would possibly understand.”

“Yes,” Lamo responded to both statements.

Coombs went on with his assessments and Lamo further confirmed a number of allegations brought up during the cross-examination. Before long the exchanges became emotional and Lamo was noticeably distraught as he answered the attorney’s inquires while sitting less than 15 feet from the man who may spend life in jail because of him. The only other time they’ve been in the same physical space occurred in late 2011 during a pretrial motion hearing that came after Manning spent nearly 10 months in essentially solitary confinement within a military jail cell in Northern Virginia.

Coombs continued to cite excerpts from the logs, asking Lamo to agree — which he always did — that those exchanges took place.

“He also told you that he had been questioning his gender for years but started to come to terms with his gender during the deployment. He told you he believed he had made a huge mess.”

“Yes,” Lamo responded on both accounts.

Manning confessed to be “emotionally crashing,” and “said he was talking to you as somebody that needed moral and emotional support,” Coombs recalled.

Again, Lamo responded affirmatively.

“At this point, you say he was trying not to end up killing himself,” Coombs said solemnly.

“That is also correct.”

“He told you that he was feeling desperate and isolated . . . Described himself as a broken soul . . . He said his life was falling apart and he didn’t have anyone to talk to . . . He said he was honestly scared . . .There was no one he could trust . . . And he told you he needed a lot of help.”

“Yes, he did,” Lamo said after each one of Coombs’

purposed pauses.

Coombs asked Lamo to confirm a number of other items from the chat logs, a rope-a-dope verbal assault that appeared to weaken the witness while exemplifying the defense’s claims that Manning only meant to help the world by going to WikiLeaks.

As the exchanges intensified, Coombs paraphrased from a now widely-quoted quip from the chat logs in which Manning proposed a hypothetical question that he hoped would elicit an answer from Lamo as to how to handle the material he encountered while deployed in Iraq and presented with access to information he never dreamed of.

“If you had free reign over classified networks for long periods of time… and you saw incredible things, awful things… things that belonged in the public domain, and not on some server stored in a dark room in Washington DC… what would you do?” the original chat quote reads.

“Do you recall him asking you that question?” Coombs asked.

“Yes I do.”

“And he told you that he thought the information that he had would have an impact on the entire world?”

“That is also correct.”

Coombs said his client believed the disclosure would reveal the truth regarding casualties in Iraq, and how the First World — the US — exploited the Third World solely for America’s own gain.

“He believed that everywhere there was a US post there was a diplomatic scandal?” said Coombs.

“That he did.”

Manning thought it was “important the info got out,” and that “it might actually change something.” It was no longer a “good guys versus bad guys” scenario in America’s wars and that he couldn’t participate in a program where innocent lives were being undervalued. Lamo agreed again on all accounts. Then Coombs painted a picture of a soldier who saw himself a humanist and valued every life on Earth — even those being slaughtered by his Army peers.

“He felt connected to everybody,” recalled Coombs.

“Yes.”

“He felt like we were all distant family.”

“Indeed.”

“And he cared.”

“Yes.”

“And he wanted to make sure that everybody was okay.”

“Yes.”

Later, Lamo admitted that Manning confided to him in the chats that the release of documents attributed to him brought “immense hope” and that, according to Coombs, “He was hoping that people would change if they saw the information.”

Then, suddenly, Coombs stopped asking questions whose answers were well documented in the chats. Before sending Lamo off the stand, he asked the witness if Manning’s remarks suggested, like the prosecutions attests, the soldier wanted to aid the enemy.

“At any time did he say he had no loyalty to America?” Coombs asked.

“Not in those words, no.”

“At anytime did he say the American flag didn’t mean anything

to him?”

“No.”

“At any time did he say he wanted to help the enemy?”

“Not in those words, no.”

“Thank you, Mr. Lamo,” Coombs concluded before the witness was permanently excused from the stand.

"He broke Adrian,” one of the dozen-or-so spectators inside of the courtroom told RT’s Andrew Blake as the session went on break. Others said that several witnesses broke into tears during the exchange between Lamo and the defense, and one struggled to find the words most appropriate to describe the moment when Lamo left the stand and walked by Manning, ignoring the soldier’s stare and exiting the room for good, likely never to be face-to-face with him again.

The government is expected to call more witnesses throughout the week who have first-hand knowledge of the early days of the Army’s criminal investigation into Manning after he was apprehended. The trial is expected to run through August.