First Amendment rights not enough to stop feds from prosecuting polygraph operators

US federal officials are investigating polygraph teachers who supposedly help job applicants fib their way through government lie detector tests. The criminal inquiry is seen as the Obama administration's latest attempt to preserve government secrecy.

Law enforcement has targeted at least two people who claim that

their methods of breath control, muscle tensing, facial tics, and

other techniques are reliable enough that an individual with a

nefarious background will be capable of gaining employment with

the US government.

Investigators accessed business records belonging to the two men,

according to a McClatchy report, and then used those documents to

identify roughly 5,000 people who sought advice on how to beat

the test. Of that sum, 20 people applied for government and

federal contracting jobs. At least ten of the 20 applicants were

eventually hired by various federal entities, including the

National Security Agency.

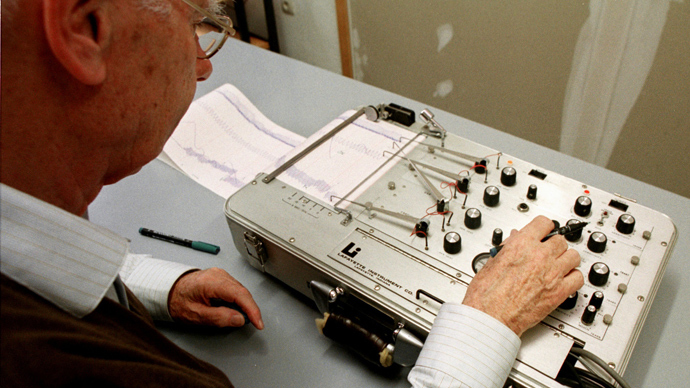

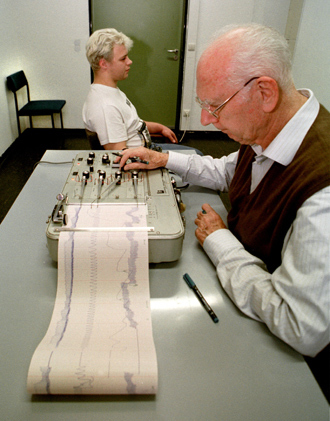

The machines were introduced in the early 20th Century, quickly

gaining favor with police who observed a suspect’s physiological

responses – including blood pressure, pulse, and perspiration –

when questioning an individual about a crime. Multiple research

studies held over the past 50 years have debated the polygraph’s

dependability, though, with a 1998 Supreme Court ruling

declaring, “There is simply no consensus that polygraph

evidence is reliable.”

Consequently, because the polygraph itself is thought to be

nonsense, experts say anyone who purports their ability to beat

it is themselves lying.

“Nothing like this has been done before,” US Customs and

Border Protection official Josh Schwartz said during a speech at

the professional polygraphers’ conference, as quoted by

McClatchy. “Most certainly our nation’s security will be

enhanced. There are a lot of bad people out there…this will help

us remove some of those pests from society.”

Federal authorities, McClatchy reported, have already arrested

Doug Williams - a former polygrapher with the Oklahoma City

Police Department who wrote a book on the subject - and Chad

Dixon of Indiana, who was the inspiration for the book. Sources

told the news agency that prosecutors will attempt to sentence

Dixon to two years in prison for wire fraud and obstructing an

agency proceeding.

Critics assert that there is simply no crime in teaching methods

to defeat the polygraph. Self-proclaimed experts freely advertise

their services online, in books, and on television, and have

never had the need to hide their services. That is not to mention

the First Amendment legal battle over impeding free speech, which

government prosecutors would surely face in court.

“If someone stabs a voodoo doll in the heart with a pin and

the victim they intended to kill drops dead of a heart attack,

are they guilty of murder?” Gene Iredale, an attorney for one

of the defendants, asked McClatchy. “What if the person who

dropped dead believed in voodoo?”

“These are the types of questions that are generally debated in

law school, not inside a courtroom,” Iredale continued.

“The real question should be: ‘Does the federal government

want to use its resources to pursue this kind of case?’ I would

argue it does not.”

Dixon, 34, refused to elaborate on his legal situation but told

McClatchy that he began working as a polygrapher because he could

not find work as an electrical engineer. The father of four

children has seen his home go into foreclosure because of the

investigation and, despite having no criminal record, he expects

to serve prison time.

“My wife and I are terrified,” he said. “I stumbled

into this. I’m a Little League coach in Indiana…never in my

wildest dreams did I somehow imagine I was committing a

crime.”