Medical first: Doctors save boy by 3-D printing airway tube

US doctors are celebrating a scientific breakthrough that may have saved the life of a baby boy.

For the first time in medical history, doctors have created an airway splint with a 3-D laser print, which was implanted into a boy whose airway kept collapsing. Kaiba Gionfriddo, a 19-month-old boy who was 3 months old when he had the operation done, was suffering from a birth defect that caused his airway to collapse nearly every day. During each incident, the baby would stop breathing, his face would turn blue, and his heart would occasionally stop. Doctors believed it was only a matter of time before the collapse of his airway would be fatal.

“Quite a few doctors said he had a good chance of not leaving the hospital alive,” April Gionfriddo, the boy’s mother, told the University of Michigan Health System for its news release on the procedure. “At that point, we were desperate. Anything that would work, we would take it and run with it.”

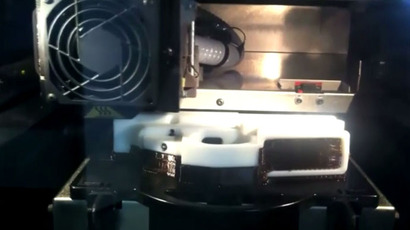

With no time to lose, doctors at the University of Michigan (UM) immediately began an attempt to build an artificial airway splint. Biomedical researchers at the university had recently obtained a new, bioresorbable device that they believed could help the boy. In just one day, they used computer-controlled lasers to print out 100 tiny plastic tubes that they stacked and fused together. The following day, the doctors implanted one of the tubes they made into Kaiba’s airway – a procedure that had never before been done.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the procedure beforehand, despite the lack of information about the effects of this process. But immediately after the tube was inserted, the baby boy was able to breathe normally.

“It was amazing. As soon as the splint was put in, the lungs started going up and down for the first time and we knew he was going to be OK,” said Dr. Glenn Green, a pediatric specialist who led the procedure at the UM C.S. Moss Children’s Hospital, in a university press release.

And after 19 months, the boy has not had a single problem with his airway, and Green told AP that “he’s a pretty healthy kid right now.”

Prior to the boy’s procedure, doctors have only ever conducted trachea or windpipe transplants using body parts from deceased donors. Occasionally, the parts were lab-produced using stem cells. But because Kaiba had an incompletely formed bronchus, those types of procedures were not suitable to treat his condition. Most children who are born with bronchus birth defects outgrow the condition by age 2 or 3. The plastic used for Kaiba's airway splint degrades over time and is gradually absorbed by the body, allowing the healthy tissue to replace it.

About 2,200 babies are born in the US each year with the condition known as tracheobronchomalaci, but few are as serious as Kaiba’s. The new technology could potentially help thousands of children breathe normally until healthy body tissue replaces the defect.

“I can think of a handful of children I have seen in the last two decades who suffered greatly… that likely would have benefited from this technology,” Dr. John Bent, a pediatric specialist at New York’s Albert Einstein College of Medicine, told AP.

Scott Hollister, Ph.D., a professor of biomedical engineering at UM, said that his involvement in the procedure is the highlight of his career.

“To actually build something that a surgeon can use to save a person’s life? It’s a tremendous feeling,” he said in UM’s news release.

Green, the doctor who led the procedure, believes that Kaiba would most likely be dead if it wasn’t for the implanted airway splint.

“He was imminently going to die,” Green said. “…I’ve seen children die from it. To see this device work, it’s a major accomplishment and offers hope for these children.”